Policy Briefs

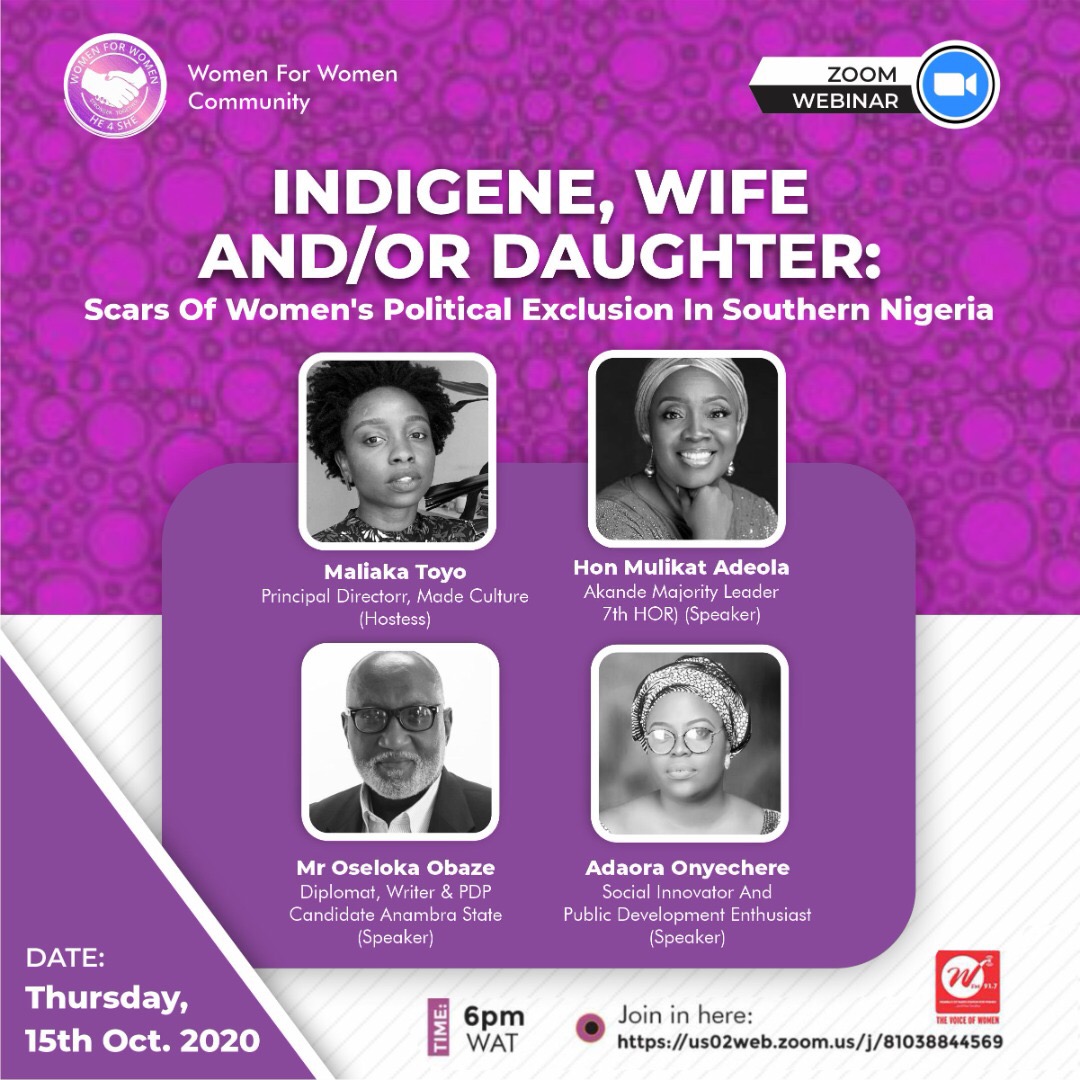

INDIGENE, WIFE AND/OR DAUGHTER: SCARS OF WOMEN’S POLITICAL EXCLUSION IN SOUTHERN NIGERIA

- October 15, 2020

- By Oseloka Obaze, MD & CEO

- 0 Comment

Remarks by Mr. Oseloka H. Obaze, MD/CEO Selonnes Consult, during the Women for Women Community Zoom Webinar Session, At 6:00 p.m. Thursday 15 October 2020

Introduction

Across the globe, women make up majority of the World’s poorest and least educated. Nowhere is this reality and demographics most stark, than in Africa and in Nigeria, where gender disparity is egregiously pronounced in political and leadership positions. There has been an obvious gender inequality in the political space. While globally women do not have the corresponding representations in political offices, even in the old and established democracies like the United States and the United Kingdom, comparatively, the participation of Nigerian women in politics remains quite abysmal. Thus in Nigeria gender mainstreaming and gender parity seems more like badly overworked clichés.

In Nigeria gender imbalance is real, but more so in politics and elective offices. It is not surprising, therefore, to find that women do not play a very active role in Nigerian politics. This however, does not mean that women have not made remarkable contributions to Nigerian politics. Many women in Nigeria have made impressive contributions in the political arena and some continue to do so. We can think of Magaret Ekpo, Mrs Funmi Ransome Kuti and others. Today my State, Anambra, has two female senators. Yet, Nigerian women suffer from two existential wounds: disenfranchisement of hereditary property rights and orchestrated exclusion from politics. Both are morally and institutional wrong; both have left scars and needs to be redressed.

Confronting a curious paradox

We face a paradox. While participation in politics is voluntary, for most Nigerian women participation is involuntary. Circumstances beyond their control make it so. For instance, there is a stark dichotomy between a woman’s right to bear children for her husband, including heirs and her political aspirations; yet the same woman cannot run for public office in her state of marriage. Most return to their state of origin to realize their political aspirations. We are witnesses to female judges being sidelined from assuming the position of Chief Judge, simply on account of not being from a state by birth and not being an indigene. This is a matter best addressed by a two-track policy change; we need to scrap “State of Origin” as an administrative fiat and in its place, introduce a “Residency law”. Such a policy shift will not just benefit women, but every Nigerian.

Since our focus is Southern Nigeria, I will look closer to home. The first southeastern commissioner, Flora Nwapa was appointed in 1970 in the then East Central State during the Gowon Administration. It then took several years before more women were appointed into the political space. A good example is the case of late Prof. Mrs Dora Akunyili, whose father so much believed in her capabilities right from childhood and encouraged her to be the best she could, by excluding her from home and kitchen activities. We all know her achievements in Nigeria and as a southeastern woman. Yet again, today in Nigeria, women are generally sidelined from holding political offices; and even appointive professional positions earned by merit or seniority are under attack.

It’s noteworthy, but sad, that since independence in 1960, through the Second Republic (1979-1983), and the return to participatory democracy in Nigeria in 1999, and indeed till date, not a single female has been popularly elected governor in any of the thirty-six states. In the 2019 general elections, “out of the 1,067 candidates cleared by Independent Electoral Comission (INEC) to participate in the governorship elections, only 80 (7.5%) were females…[and] 35 of them are from the north, while 45 are from the southern part of Nigeria.” Unsurprisingly, none of the women won.

Exclusion of women from this politics, and how to vanquish it, is something I’m proud to say we have studied closely in my consultancy firm, and in July 2019, published our report (Vanquishing Gender Imbalance in Nigerian Politics), in which we made broad policy recommendations. I am involved because I have several sisters and two daughters, who can hold their own in their career choices. When I ran for governor in Anambra 2017, my running mate was a woman. It bears asking then, what the geneses of political exclusion are. Four factors –culture, religion, education, governance and policy—are key contributors to marginalization of women in politics. We can also add lack of political will to the list.

It’s most ironical that women make up 52% of the voting population in Nigeria, yet cannot rally to elect their fellow women into public offices. Part of the challenge is anecdotal. The nature of politics played in Nigeria discourages women from participating actively. Power connections, political manipulations, financial patronage are preferred over merit. But then again, most women in politics often forget they are women and start acting and behaving like men. This can put off followers, supporters and aspirants.

While most women organizations in Nigeria continue to push for constitutional provisions that allows for better representation by allocating 35% affirmative action for women at the federal level and 20% at the state level, we are confronted by stark reversals. Indeed, the gains made during the Jonathan administration on women representation appears lost. The reason is that we continue to fail to incentivize women sufficiently, even as we recognize them as bedrocks of our families. Variables and causative factors responsible for such imbalance are multi-dimensional, but as I mentioned earlier, these are traceable to culture, religion, education, and governance.

Exclusion of women in southern Nigeria hinges mainly on culture

In southern Nigeria, which is our focus today, general societal bias, culture and tradition continue to result in many life-long scars. Culture is a predominant factor. Male counterparts are always preferred from childhood. Female children are often intimidated -explicitly or implicitly – into assuming subsidiary roles in the family; females are only allowed to play the ‘female role’. When a family has only female children, it is believed that they are bereft of children. Even some women with good educational background who venture into politics and public life, are subjected to lots of trauma via hubris by their male counterparts, and at times, even by their own husbands. Besides being women leaders, no Nigerian woman has chaired a major Nigerian political party.

In the indigenous rural areas, the role of the woman is still perceived to be in the kitchen or that proverbial “other room.” Hence those consigned to upholding Family Life values – as the keepers of home, kitchen and baby making hardly aspire to politics. Finally, politics Nigeria is capital intensive, as such financial strength is critical in effective political participation. Women are expected to play the mothering role at home, while the men are the breadwinners. Since culturally women are not really expected to earn money -even where the reality proves to be the opposite- it means they have limited resources for politics. In truth, also, women would rather dedicate their hard-earned resources to family upkeep than fritter it away on politics.

Excluding women from politics has discernible implications. Largely, they are unable to advance women’s rights in areas such as violence against women, healthcare services, family policy, gender and income parity; support budget in health and education; contribute to promoting democratic dividends; undertake advocacy measures aimed at citizen’s social welfare needs and quality of life; and help in promoting peace and security and conflict resolution.

The way forward

In 2012, a UK Department of International Development (DFID) stated that “Women are Nigeria’s hidden resource.” That finding has not changed. As Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the first woman to be elected head of state in an Africa country rightly reminds us, we need an innovative and flexible approach to women’s inclusion, not just in peace mediation, but in politics, governance and nation-building. In her words, “We need to promote the kind of equality we know brings balanced development and peace.”

We need to acknowledge that our world and nation would be better, if we evolved and gave women more prominent roles in politics and as change agents. As such, the beginning of female orientation towards active politics should start in early childhood years, well before age 16. If the girl-child is constantly reminded that she could achieve as much as she aspires to and desires in the society; then she begins to believe in the infinite possibilities of her efforts.

From our study, we were of the view that “vanquishing the persisting imbalance in Nigerian politics requires a dual track approach consisting of governmental statutory actions, as well as proactive constructive engagement by all the registered Nigerian parties.” It is one thing to have a national gender policy; it’s another thing altogether to have it fully domesticated and implemented. Nonetheless, it would be up to the women to do the heavy lifting in terms of advocacy and demands; I’m certain they will find willing allies among the men folk. [End]

- Post Categories

- Anambra

- Capacity building

- Culture

- Gender inclusion

- Gender mainstreaming

- Gender parity

- Gender Policy

- Girl-child

- Lady Chidi Onyemelukwe

- Leadership

- Nigeria

- Party politics

- Political exclusion

- Political inclusion

- Politics

- Senator Stella Oduah

- Senator Uche Ekwunife

- Women for Women

- Women in politics in Nigeria

- Youth

Oseloka Obaze, MD & CEO

Mr. Obaze is the former Secretary to the State Government of Anambra State, Nigeria from 2012 to 2015 - MD & CEO, Oseloka H. Obaze. Mr. Obaze also served as a former United Nations official, from 1991-2012, and as a former member of the Nigerian Diplomatic Service, from 1982-1991.

Tags

Welcome to Selonnes Consult / OHO and Associates

Selonnes Consult Ltd. is a Strategic Policy, Good Governance and Management Consulting Firm, founded by Mr. Oseloka H. Obaze who served as Secretary to Anambra State Government from 2012-2015; a United Nations official from 1991-2012 and a Nigerian Foreign Service Officer from 1982-1991.

Recent Posts

- Policy Brief No. 24-7| Overcoming Nigeria’s Legacy of Woes

- Policy Brief No. 24-6| Nigeria’s Not Too Big To Fail By Oseloka H. Obaze

- Policy Brief No. 24-5 | Nigeria’s Opposition Abet APC’s Grim Governance

- Policy Brief No. 24-4 |Blame Game Is Not Policy Game

- Policy Brief No. 24-3 | Implementing Oronsaye Report – No Walk in the park..

Categories

- #BuFMaNxit

- #EndSARS

- 2020 appropriations

- 2023 Appropriations

- 2023 buget estimates, 2024 budget estimate, FGN

- 2023 Liberian general elections

- 2024 Approriations

- Abia State

- Abuja

- Afghanistan

- Africa

- Africa’s largest economy

- AGF Malami

- Agonizing reprisals

- Alumni Association

- Aminu Waziri Tambuwal

- Amotekun

- Anambra

- Anambra Integrated Development Strategy

- Anambra state

- ANIDS

- Announcement

- Announcements

- Anonymous

- Apartheid

- APC

- APC, continuity in governance, budget performance

- Atiku Abubakar

- Bad Governance

- Bandits

- Beyond oil economy

- Bi-partisan caucus

- Biography

- Boko Haram

- Bola Tinubu

- Book Review

- Budget making

- Buget Padding

- Buhari

- Building Coalition

- Bukola Saraki

- Burkina Faso

- CAC

- Capacity building

- Capital Flight

- Career Counseling

- Central Bank of Nigeria

- Central Minds of Government

- Chief Security Officers

- Chieftaincy

- China

- Chinese doctors

- Chinua Achebe

- Civil Service reform

- Civil Society

- Civilian joint task force

- CKC Onitsha

- Clientel

- Climate Change

- Community policing

- Community resiliency

- Community transmission

- Conferences

- Consitutional Reform

- Constitutional Rights

- COP28

- Corona Virus Facts

- Corporate Exits,

- corporate social responsibility

- Cost of governance

- Coved 19 management

- Covid 19 Case Load

- Covid 19 vaccine policy

- Covid-19

- Cross political tier aspirations

- CSOs

- Culture

- Curriculum Vitae

- Customer Relationship

- Cutting Cost of Governance

- Cyril Ramaphosa

- Democracy

- Demolitions in Nigeria

- Development

- Disaster response

- Diseent

- Domestic terrorism

- Donald Trump

- Doublethink

- Ebola

- Economic Policy

- Economy

- ECOWAS

- Education

- Elections

- EMS

- Enabling environmrnt

- Endogenous solutions to conflict

- EndSARSnow

- Enugu state

- Environment

- Environmental degredation

- Escalatory measures

- EU

- Events

- Executive Order No. 5

- Fake news

- Fake news versus freedom of speech

- Farmers/Herdsmen conflict

- Fatalities

- Faux Policies

- FGN

- First Responders

- Fiscal Policy

- Fishermen

- Flooding

- Food security

- Forced Removals

- Foreign exchange

- Foreign Policy

- Full disclosure

- Gen Soliemani

- Gender inclusion

- Gender mainstreaming

- Gender parity

- Gender Policy

- General News

- Generator Country

- Genocide

- Girl-child

- Global best practices

- Global Compact

- Global housing crisis

- Global insecurity

- Global pandemic

- Global respone

- Good Governance

- Grazing areas

- Groupthink syndrome

- Habitat

- Hate Speech

- Herdsmen

- Hisbah security outfits

- History

- Housing Deficit

- human capital

- Human development capital

- Human rights violations

- Human Security

- IGR

- INEC

- Insecurity

- Inter-community conflicts

- International relations

- Interview

- iOCs

- Iran

- Iraq

- Joe Biden

- Joe Garba

- Judiciary

- Kamala Harris

- Kankara

- Kano

- Kaño State

- Katsina State

- Kidnapping

- King Louis IX.

- Kofi Annan

- Labour Unions

- Lady Chidi Onyemelukwe

- Lagos

- Leadership

- Leadership hubris

- Legislative oversight

- Lesotho

- Libel

- Liberia,

- Literary Event

- Lock down

- Malgovernance

- Mali

- Media

- Media accountability

- Migration

- militancy

- Military coups in Africa

- Millennium Development Goal

- Minister of Health, Dr Osagie Ehanire

- Misgovernance

- Mitigation

- MNCs

- Motivational Speeches

- Muhammadu Buhari

- NAFDAC

- NASS

- Nation building

- National interest

- National resiliency strategy

- National Security

- Nationalists,

- NATO

- Natural Disaster

- NCDC

- NDA – the Nigerian Defence Academy

- NEMA

- New York Times

- Niger

- Niger Delta

- Nigeria

- Nigeria Medical Association

- Nigerian Economy

- Nigerian elite, democracy

- nigerian military

- Nigerian Senate

- Nigerian Society of Writers

- Nigerian Supreme Court.

- Nigerian Youth

- Nigerian-German relations

- NMA

- Nobel Peace Prize

- Non-state actors

- Novel corona virus

- Obituary

- oil prices

- Oil subsidy

- Onitsha

- Op-Ed.

- Operational Activities

- Opposition Politics

- Oronseye Report

- Oseloka H. Obaze

- Pacesetter Frontier Magazine

- Palliatives

- Pandemic

- Party politics

- Party Politics In Africa

- Pastoral Conflict

- PDP

- PDP Governorship Candidate

- Peace and security

- PENCOM

- Pension contributions

- Peter Obi

- Petroluem policy

- philosophy

- Piracy

- Police Brutality

- Policy Brief

- Policy Making

- Policy transparency

- Political Economy

- Political economy.

- Political exclusion

- Political inclusion

- Politics

- Power and Energy

- Press Remarks / Press Releases

- Preventive measures

- Prime Witness book presentation

- Proactive Policing

- Promotions & Offers

- Public Notice

- Quarantine

- R & D

- Racial inequality

- Regional blocs

- Regional hegemon

- Regional security network

- Regulatory Policies

- Renewable energy

- Research and development

- Responsibility to protect

- Restructuring

- Rule of law

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Safety Net Hospital

- Saigon

- SARS

- SDG

- Seasonal Floods

- Security

- Sedition

- Selonnes Consult

- SEMA

- Senator Hope Uzodinma

- Senator Stella Oduah

- Senator Uche Ekwunife

- Separation of Powers

- Services

- Shale tecnology

- Shelter in Place

- Six geopolitical zones

- SMes UNIDO

- Social distancing

- Society for International Relations Awareness (SIRA)

- South Africa

- Southeast Nigeria

- Special Intervention Programme (SIP)

- Speeches

- State police

- State vigilantes

- Stay at home order

- Stay home orders

- Strategic planning

- Strength of Government

- Tampering with free speech

- Taxes

- Technology

- Tecnology

- The Blame Game

- The Peter Principle

- The Policy Game

- Think Tank

- Three Arms of government

- Three Tiers of Government

- Treason to the Constitution

- Tributes

- Tweets

- U.S.

- UN

- UN peacekeeping

- UN sanctions

- Uncategorized

- UNEP

- Ungoverned space

- Ungoverned space,

- United Nations

- United States

- Unity Party of Liberia

- Upcoming Events

- US strategic interest

- Value added tax

- Wale Edu

- Ways and Means

- West Africa and Sahel

- White House

- Women for Women

- Women in politics in Nigeria

- World Bank

- Xenopbobia

- Yemi Osinbajo

- Youth

- Zoning,

Archives

- June 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- July 2015

Contact Info

MD & CEO

Oseloka H. ObazeA301 Chukwuemeka Nosike Street, Suite # 7, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria

Phone: NG: 0701-237-9333Mobile: US: 908-337-2766Email: Selonnes@aol.com, Info@selonnes.com