Policy Briefs

Selonnes Consult Policy Brief 62/19: Receding, Emerging and Resurging Issues and Trends in the Security Sector

- June 20, 2019

- By Oseloka Obaze, MD & CEO

- 0 Comment

Paper Presented by Mr. Oseloka H. Obaze, MD/CEO of Selonnes Consult, Awka, Nigeria At the CISLAC-FES Multi-Stakeholders Forum on Peace and Security Challenges in Nigeria, At the Consort Luxury Suite and Hotels, Abuja, FCT 20 June, 2019.

Introduction

I am very honoured, pleased and grateful to have been invited by CISLAC and FES to offer my perspectives on “Receding, Emerging and Resurging Issues and Trends in the Security Sector.” As one of the “least peaceful places on earth,” Nigeria is inevitably security challenged. Presently, no national interest issue – not elections and not restructuring – has singularly dominated Nigeria’s political and socio-economic discourse as much as insecurity. Concerns about security sector dynamics in Nigeria – including the understanding, perceptions, realities and related costs – are all too palpable, more so with the government’s antipathy towards informed public outcry and expressed concerns.

No nation is insulated from security challenges. The difference is that some nations have developed better response systems and mechanisms. Nigeria’s system and modalities for responding to security issues focus on “safeguarding” establishment and policy options that are not working as they should. Beyond that, we engage in blame games, even though we know what the problems are.

Increasingly, concerns are being expressed of a diametric failure in the security sector; the emergence of ungoverned spaces, and indeed, of governmental “crude surrender” to security threats posed by militancy. As regards ungoverned spaces, experts point to “a direct reflection of the inability of the state to effectively perform its minimal statutory functions.” This amounts also to a failure to undertake fully, the states’ responsibility to protect its citizens. The paradox is that “ungoverned spaces” can exist in “strong” states, in “urban environments” and “not just in rural areas” alone.

The emerging trends and dynamics point to evident fluidity, in the threats and challenges, policy dissonance and limitations in our response capability. The inability to tackle security in all its ramifications often becomes an overarching factor. Paradoxically, Nigeria’s much-touted security sector reforms seem to have yielded less than the desired results. A recent report from the Nigeria Security Tracker shows that no fewer than 25,794 Nigerians may have died in violent crises in the first four years of the Buhari Administration.

What we can all agree to – and there are vast areas of disagreement – is that given the prevailing nature and scope of insecurity in Nigeria, there exist some “receding, emerging and resurging issues and trends in the security sector.” Overall, insecurity has been incremental. Admittedly, the present disconcerting scope has its genesis in the failure of successive governments. These trends are multidimensional, but there is also a shared commonality of felt sense of bleakness, imminent threat and present danger. Another broadly shared view is that presently, “very few parts of Nigeria are exempt from menace of banditry and kidnappings.” Policy miscue and a troubling dismal response, relative to kidnapping, oil theft, militancy, and herders violence, conveys the impression that the federal government is wittingly engaged in the “beatification of stealing” and “pacification” of violent and pillaging herdsmen.

Changing Nature of Security Trends

Globally, and in Nigeria, the nature of insecurity and the methodologies required for tackling them have metamorphosed. “In the place of the former form of violence came election-related violence, long-standing ethno-national conflict, drug trafficking, maritime piracy, extremism, youth inclusion, migration, the rapid development of extractive industries and land management etc.” Related “manifestations include attacks on shipping, sabotage of hydrocarbon infrastructure, and maritime and resource theft.” In response to security challenges, Nigeria now resort to multilateral measures and mechanisms, such as the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) to tackle Boko Haram, and the ECOWAS Integrated Maritime Strategy (EIMS) and the Gulf of Guinea Yaoundé Code of Conduct to tackle piracy.

Domestically, the government continues to deploy variants of military operations to tackle insecurity. As my colleague, Ejeviome Eloho Otobo and I observed in a recent policy brief, “While the military may offer “hard power” security, they are not equipped or trained to undertake or play the “soft power” role that other institutions can provide, including civilian police problem solving duties.”

But what are the identifiable traits of “receding, emerging and resurging issues and trends in the security sector?” Six critical and identifiable drivers of violent conflicts and thus insecurity, include “lack of quality governance and transparency, ethnic rivalry, religious extremism, mismanagement of land and natural resource, declining economic conditions and proliferation of small arms and light weapons.” These “indicators of conduciveness” are all prevalent in Nigeria. Their cumulative negative impact are further exacerbated by other variables, which include, lack of state penetration, lack of state monopoly of force, lack of border controls, external interference, demographics, possession of adequate infrastructure and adequate funding by the rogue non-state actors.

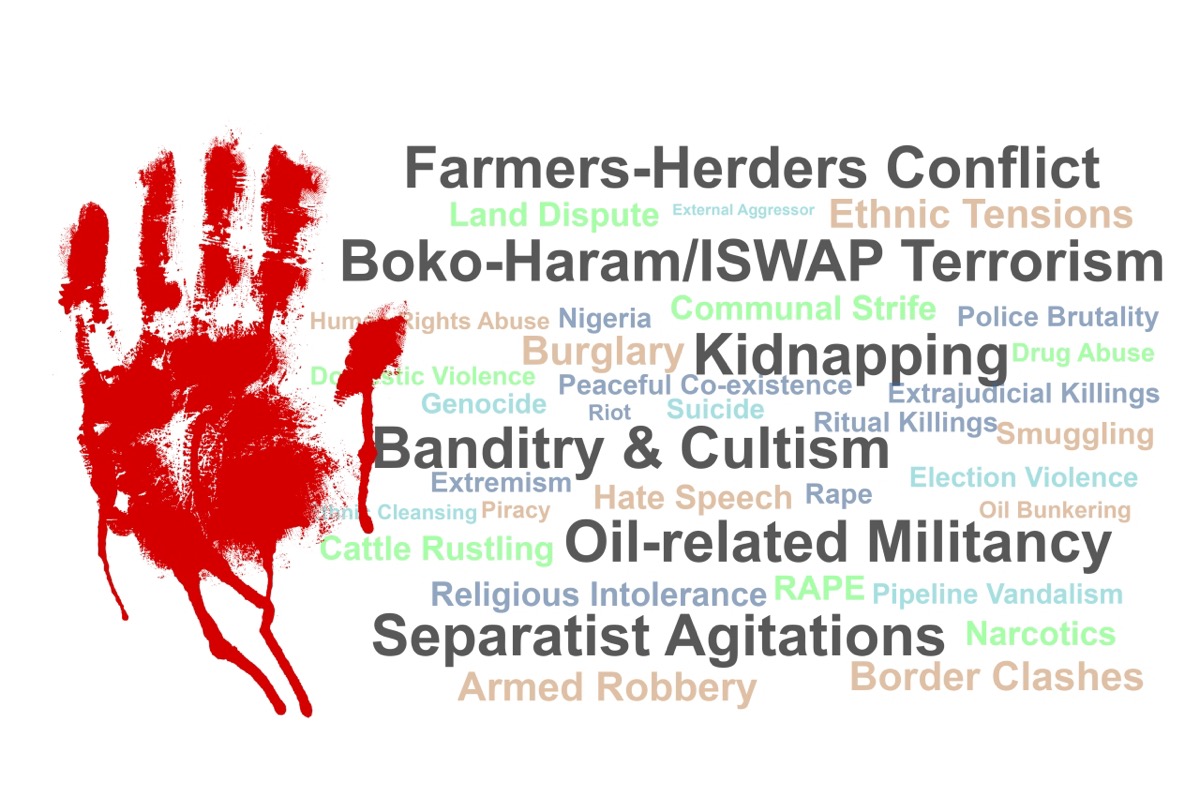

I consider the six most dominant security issues and trends in Nigeria, to be; Farmers-Herders Conflict, Boko-Haram/ISWAP Terrorism, Kidnapping, Banditry and Cultism, Oil-related Militancy, and Separatist Agitations. Hence, I will attempt to offer a synoptic overview of these trends.

Farmer/Herder Conflict

Violent clashes between herders and farmers remain a major source of conflict and insecurity in Nigeria. Government’s pandering to Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria (MACBAN) and its seeming unwillingness to deal decisively with herdsmen violence has come under scrutiny. Such policy pussyfooting has allowed the conflict to fester. Inaction on the part of the government is perceived as exacerbating the crises. Meanwhile, the national death toll is spiraling upwards; “some 3,641 people died in the clashes from 2015 to late 2018.” Presently the fatalities are well over 4,000 lives. The expanding conflict has contributed to an unprecedented rise of insecurity. The resultant effect of Boko Haram and herdsmen attacks have also resulted in an unprecedented level of peacetime internally displaced persons (IDPs), now estimated at two million.

Boko Haram and Islamic State’s West Africa Province Growing Impetus

The fight against Boko Haram is mutant. While the Boko Haram attacks on soft targets may have waned and receded, yet we have witnessed an upsurge in its attacks on military installations. The Nigerian military now seems to be its primary target, perhaps with a focus on capturing armaments. The general perception – one induced by government – persist that Boko Haram stands degraded. Such assumptions border on establishment delusion. As experts observe, Boko Haram “has suffered significant conventional military defeats and lost most of the territory it loosely controlled in late 2014, [but,] despite this, it is not a spent force and continues to exact an unacceptable humanitarian toll.” It’s on record that during Buhari’s first term, a period of four years, “Boko Haram has attacked and sacked 22 military posts” killing scores of Nigerian soldiers.

Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP), as splinter of Boko Haram – is now in its seventeenth year. Its activities are no longer considered as “emerging” but rather resurgent. Recently, ISWAP attacked a Nigerian Army Base in Kareto, in the Mobbar Local Government area of Borno State, sacking it completely and killing the Commanding Officer of the 158 Battalion and some of his troops. We cannot overlook the fact that BH/ISWAP profits from prevailing economic situation and shrinking legitimate windows of opportunity. Already there is an easy pool of a large swathe of impressionable and unemployed youths to exploit. So long as the funding and rearmament of these two entities are not determined and curtailed, their activities will not abate.

Kidnapping and Oil-related Militancy

Well beyond its most debilitating and destructive phase, militancy in the south-south is clearly “receding”. Ironically, the downturn is not an attribute of any governmental action or pushback, but for other reasons. Militants and the government seem to have found a dubious common ground; crude oil theft has become expansive. Militants, who hitherto engaged in disruptive attacks of national oil facilities with deleterious effect on the economy, presently resort to less disruptive activities of making money from crude oil theft. For its part, the government has also opted for this route of least resistance. As a recent Bloomberg analysis indicates, Nigeria loses about 100,000 barrels per day. This number pales significantly to the disruption levels reached at the peak of militant activities a few years ago. As the report contends, “the Federal Government is accepting oil theft because it is less injurious than militancy.” This reality represents emerging trends of “cutting losses” or accepting the “cost of doing business”. In reality, the present disposition is unsustainable and will prove economically deleterious in the long run. The absence of strong deterrence is an indirect invitation to more criminals to join the kidnapping and oil theft fray.

Banditry/Cultism

A clear nexus exist between the twin scourge of banditry and cultism and represent an expanding component of outlawry in Nigeria and governance failings. Some have advanced the linkage to include extreme poverty. Whereas cultism is receding in our tertiary institutions, it is has found troubling expression elsewhere – our homesteads and villages. As an emerging trend, cultism has “relocated from tertiary institutions’ campuses where it hitherto holds sway to the streets in various communities across the country.” Some observers have tried to connect the dots between cultism in tertiary institutions and poverty. And some have argued that cultism is “something that cannot be separated from the poor environment where students live and learn.”

There is an added dimension and corollary; cultism promotes human insecurity and vice versa. With youth unemployment hovering around 30%, the assertion by Andrew Nevin, that “being young in Nigeria is very challenging,” assumes a damning and insidious meaning. That challenge as it pertains to cultism is increasingly manifesting openly on our streets, secondary schools and youth hangout joints. Along with the expansion comes diminished value of life. Yet, whether one speaks of banditry or cultism in Nigeria, we ought to be cognizant that “in reality, the usage conflates two underlying problems – ineffective law enforcement in Southern Nigeria and the crisis of ungoverned spaces in Northern Nigeria.”

Separatist Agitations

From independence, Nigeria has struggled with “the challenge of how to coalesce the numerous ethnic nationalities in the country into one united nation.” Presently, despite exhortations and protestations, little or no attention is being accorded to the ethnic proclivities of the Nigerian state. That Nigeria continues to encounter trenchant calls for restructuring and separatist agitation is indicative of simmering discontent. Resurgent calls for Biafra are now complimented by calls for Oduduwa Republic, Arewa Republic, and Niger Delta Republic. In April 2015, Oba Rilwan Akiolu of Lagos threatened that Igbo residents of Lagos state should be ready to “perish inside the lagoon,” if they do not vote for the ruling APC government in the State. The agitation and push back reached a new zenith on 17 June, 2017, when Arewa Youths, in the so-called Kaduna Declaration, gave the Igbo people resident in the north a “quit notice.” These events underpin existing separatist fault lines.

Beyond cultural diversity, the causes and trajectories of separatism are all too obvious. A lingering sense of non–inclusion – real or imagined – compels the agitation for separation. Implementing constitutionally ordered federal character and balanced ethnic representation remains a national challenge. The political willingness to address the separatist agitations robustly seems lacking as evidenced by the recent “unbalanced” leadership change in the legislative arm of government, which have only aggravated this insensitivity. Such are part of the feelings that undergird the separatist agitations. If the status quo prevails, we can anticipate a resurgence of separatist agitations. This is to be expected mainly from the south east. Of late, such agitations are increasing; “in the south-west and virtually all other parts of the country.” The increasing despondency and the tempo, with which separatism is being discussed, even if in hushed tones, should worry Nigeria’s policymakers. The jackboot approach – Nigeria’s preferred policy response to such national interest issues – has always yielded limited results. Its ephemeral impact of momentarily quelling such agitations, only elicit more fervent agitations further down the road.

In summation I will make six (6) suggestions on how best to grapple with some of our existing security challenges.

▪ Good Governance: The best security architecture is that anchored on effective statecraft and good governance. The plethora of security challenges confronting Nigeria is symptomatic of her dysfunctional structural problems. Grappling with security challenges, regardless of the scope requires a fine-tuned introspective process that combines legislative and executive “soft power” with military “hard power” in tackling security challenges. It remains an anomaly to use the military for purely civilian police duties. That mindset must change. State policing will improve collaboration.

▪ Strong Institutions: Entrenching an operational and holistic security architecture that serves common cause, requires our cracking the code of guaranteeing the sanctity of state institutions. To guarantee strong and secure state institutions that will address our security concerns requires striking a delicate balance between working together and yet insulating important state institutions like the judiciary, the electoral umpire, security and regulatory agencies from undue political interference. Most existing institutions suffer organizational, operational and command deficit and are thus ill-adapted to emergent challenges.

▪ Inter-agency Collaboration: Nationally, we lack institutional synergy. Unhealthy rivalry between security agencies that need to complement each other remains a bane, despite clear delineation of statutory functions. Hence, greater emphasis must be placed on intelligence sharing as a means of squaring up to the multi-faceted challenges. Our intelligence and security agencies cannot afford to work at cross purposes or engage in turf fights. It is left for the executive to provide the needed leadership and direction. The legislature, for its part, must provide the enabling laws, while the judiciary should address concerns and guarantee the protection of ordered liberties where and when the lines blur.

▪ Bilateral/Multilateral Cooperation: Some of Nigeria’s most demanding security flashpoints are domiciled along our national borders. Security challenges, notably terrorism, piracy, militancy, and oil theft, occur within or in proximity to international boundary areas. The current practice of deploying the Multinational Joint Task Force (MJTF) to tackle Boko Haram, and the use of ECOWAS Integrated Maritime Strategy (EIMS) and the Gulf of Guinea Yaoundé Code of Conduct to tackle piracy, should be sustained. Joint operations and training with our neighbours need to be increased.

▪ Ramping Up Intelligence Gathering: There can be no security without unfettered intelligence gathering. In Nigeria, community and institutional distrust and meddling undermine security. The concern for anonymity and witness protection also needs to be taken more seriously if we are to see improvements in the voluntary surrender of intelligence to security agencies.

▪ Enhanced Technology: Advances in technology continue to broaden security methodologies and policy options available to policymakers. Artificial intelligence and drone surveillance are emerging methods and examples of technological advances open to Nigeria for assessing security threats. Additionally, Nigeria can only do so much without an enhanced and integrated identity management system.

▪ Robust Training: There is no substitute for adequate training and professionalism for security agents. Only a robust training regime and full immersion of security agents in the extant protocols via civilian engagement orientation courses, will guarantee commensurate collaboration from the national population. The national landscape will benefit immensely from reduced incidences of excessive use of force, high handedness and human rights abuse witnessed during military interventions in civilian policing. Transparent reprisals for those in breach of such rights will further boost confidence and collaboration.

Conclusion

Absence of political will and purposeful leadership will continue to impact negatively on how we respond to receding, resurging and emerging security issues. Dangers posed by emerging conflicts are as bad as those arising from recidivism. We must be cognizant that for our security mechanisms to be efficacious and “for security to last, we have to move from safeguarding it to actively promoting it.” We must also eschew divisive rhetoric and avoid sectionalizing security threats and challenges. “The use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in the provision of solution to human, social and industrial challenges has proven success in many nations and Nigeria should not be an exception.” Additionally, we need to find ways of regaining the public trust and confidence on critical national security issues. Convening proactive stakeholders’ dialogue forum such as this will be of great utility. But more broadly, we must seek solutions that serve national interest in the short, medium and long term.

END NOTES

Oseloka Obaze, MD & CEO

Mr. Obaze is the former Secretary to the State Government of Anambra State, Nigeria from 2012 to 2015 - MD & CEO, Oseloka H. Obaze. Mr. Obaze also served as a former United Nations official, from 1991-2012, and as a former member of the Nigerian Diplomatic Service, from 1982-1991.

Welcome to Selonnes Consult / OHO and Associates

Selonnes Consult Ltd. is a Strategic Policy, Good Governance and Management Consulting Firm, founded by Mr. Oseloka H. Obaze who served as Secretary to Anambra State Government from 2012-2015; a United Nations official from 1991-2012 and a Nigerian Foreign Service Officer from 1982-1991.

Recent Posts

- Policy Brief No. 24-7| Overcoming Nigeria’s Legacy of Woes

- Policy Brief No. 24-6| Nigeria’s Not Too Big To Fail By Oseloka H. Obaze

- Policy Brief No. 24-5 | Nigeria’s Opposition Abet APC’s Grim Governance

- Policy Brief No. 24-4 |Blame Game Is Not Policy Game

- Policy Brief No. 24-3 | Implementing Oronsaye Report – No Walk in the park..

Categories

- #BuFMaNxit

- #EndSARS

- 2020 appropriations

- 2023 Appropriations

- 2023 buget estimates, 2024 budget estimate, FGN

- 2023 Liberian general elections

- 2024 Approriations

- Abia State

- Abuja

- Afghanistan

- Africa

- Africa’s largest economy

- AGF Malami

- Agonizing reprisals

- Alumni Association

- Aminu Waziri Tambuwal

- Amotekun

- Anambra

- Anambra Integrated Development Strategy

- Anambra state

- ANIDS

- Announcement

- Announcements

- Anonymous

- Apartheid

- APC

- APC, continuity in governance, budget performance

- Atiku Abubakar

- Bad Governance

- Bandits

- Beyond oil economy

- Bi-partisan caucus

- Biography

- Boko Haram

- Bola Tinubu

- Book Review

- Budget making

- Buget Padding

- Buhari

- Building Coalition

- Bukola Saraki

- Burkina Faso

- CAC

- Capacity building

- Capital Flight

- Career Counseling

- Central Bank of Nigeria

- Central Minds of Government

- Chief Security Officers

- Chieftaincy

- China

- Chinese doctors

- Chinua Achebe

- Civil Service reform

- Civil Society

- Civilian joint task force

- CKC Onitsha

- Clientel

- Climate Change

- Community policing

- Community resiliency

- Community transmission

- Conferences

- Consitutional Reform

- Constitutional Rights

- COP28

- Corona Virus Facts

- Corporate Exits,

- corporate social responsibility

- Cost of governance

- Coved 19 management

- Covid 19 Case Load

- Covid 19 vaccine policy

- Covid-19

- Cross political tier aspirations

- CSOs

- Culture

- Curriculum Vitae

- Customer Relationship

- Cutting Cost of Governance

- Cyril Ramaphosa

- Democracy

- Demolitions in Nigeria

- Development

- Disaster response

- Diseent

- Domestic terrorism

- Donald Trump

- Doublethink

- Ebola

- Economic Policy

- Economy

- ECOWAS

- Education

- Elections

- EMS

- Enabling environmrnt

- Endogenous solutions to conflict

- EndSARSnow

- Enugu state

- Environment

- Environmental degredation

- Escalatory measures

- EU

- Events

- Executive Order No. 5

- Fake news

- Fake news versus freedom of speech

- Farmers/Herdsmen conflict

- Fatalities

- Faux Policies

- FGN

- First Responders

- Fiscal Policy

- Fishermen

- Flooding

- Food security

- Forced Removals

- Foreign exchange

- Foreign Policy

- Full disclosure

- Gen Soliemani

- Gender inclusion

- Gender mainstreaming

- Gender parity

- Gender Policy

- General News

- Generator Country

- Genocide

- Girl-child

- Global best practices

- Global Compact

- Global housing crisis

- Global insecurity

- Global pandemic

- Global respone

- Good Governance

- Grazing areas

- Groupthink syndrome

- Habitat

- Hate Speech

- Herdsmen

- Hisbah security outfits

- History

- Housing Deficit

- human capital

- Human development capital

- Human rights violations

- Human Security

- IGR

- INEC

- Insecurity

- Inter-community conflicts

- International relations

- Interview

- iOCs

- Iran

- Iraq

- Joe Biden

- Joe Garba

- Judiciary

- Kamala Harris

- Kankara

- Kano

- Kaño State

- Katsina State

- Kidnapping

- King Louis IX.

- Kofi Annan

- Labour Unions

- Lady Chidi Onyemelukwe

- Lagos

- Leadership

- Leadership hubris

- Legislative oversight

- Lesotho

- Libel

- Liberia,

- Literary Event

- Lock down

- Malgovernance

- Mali

- Media

- Media accountability

- Migration

- militancy

- Military coups in Africa

- Millennium Development Goal

- Minister of Health, Dr Osagie Ehanire

- Misgovernance

- Mitigation

- MNCs

- Motivational Speeches

- Muhammadu Buhari

- NAFDAC

- NASS

- Nation building

- National interest

- National resiliency strategy

- National Security

- Nationalists,

- NATO

- Natural Disaster

- NCDC

- NDA – the Nigerian Defence Academy

- NEMA

- New York Times

- Niger

- Niger Delta

- Nigeria

- Nigeria Medical Association

- Nigerian Economy

- Nigerian elite, democracy

- nigerian military

- Nigerian Senate

- Nigerian Society of Writers

- Nigerian Supreme Court.

- Nigerian Youth

- Nigerian-German relations

- NMA

- Nobel Peace Prize

- Non-state actors

- Novel corona virus

- Obituary

- oil prices

- Oil subsidy

- Onitsha

- Op-Ed.

- Operational Activities

- Opposition Politics

- Oronseye Report

- Oseloka H. Obaze

- Pacesetter Frontier Magazine

- Palliatives

- Pandemic

- Party politics

- Party Politics In Africa

- Pastoral Conflict

- PDP

- PDP Governorship Candidate

- Peace and security

- PENCOM

- Pension contributions

- Peter Obi

- Petroluem policy

- philosophy

- Piracy

- Police Brutality

- Policy Brief

- Policy Making

- Policy transparency

- Political Economy

- Political economy.

- Political exclusion

- Political inclusion

- Politics

- Power and Energy

- Press Remarks / Press Releases

- Preventive measures

- Prime Witness book presentation

- Proactive Policing

- Promotions & Offers

- Public Notice

- Quarantine

- R & D

- Racial inequality

- Regional blocs

- Regional hegemon

- Regional security network

- Regulatory Policies

- Renewable energy

- Research and development

- Responsibility to protect

- Restructuring

- Rule of law

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Safety Net Hospital

- Saigon

- SARS

- SDG

- Seasonal Floods

- Security

- Sedition

- Selonnes Consult

- SEMA

- Senator Hope Uzodinma

- Senator Stella Oduah

- Senator Uche Ekwunife

- Separation of Powers

- Services

- Shale tecnology

- Shelter in Place

- Six geopolitical zones

- SMes UNIDO

- Social distancing

- Society for International Relations Awareness (SIRA)

- South Africa

- Southeast Nigeria

- Special Intervention Programme (SIP)

- Speeches

- State police

- State vigilantes

- Stay at home order

- Stay home orders

- Strategic planning

- Strength of Government

- Tampering with free speech

- Taxes

- Technology

- Tecnology

- The Blame Game

- The Peter Principle

- The Policy Game

- Think Tank

- Three Arms of government

- Three Tiers of Government

- Treason to the Constitution

- Tributes

- Tweets

- U.S.

- UN

- UN peacekeeping

- UN sanctions

- Uncategorized

- UNEP

- Ungoverned space

- Ungoverned space,

- United Nations

- United States

- Unity Party of Liberia

- Upcoming Events

- US strategic interest

- Value added tax

- Wale Edu

- Ways and Means

- West Africa and Sahel

- White House

- Women for Women

- Women in politics in Nigeria

- World Bank

- Xenopbobia

- Yemi Osinbajo

- Youth

- Zoning,

Archives

- June 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- July 2015

Contact Info

MD & CEO

Oseloka H. ObazeA301 Chukwuemeka Nosike Street, Suite # 7, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria

Phone: NG: 0701-237-9333Mobile: US: 908-337-2766Email: Selonnes@aol.com, Info@selonnes.com