Policy Briefs

Snapshot Of A Moving Target: A Review Of Oseloka Obaze’s Prime Witness: Change & Policy Challenges in Buhari’s Nigeria (2017).

- May 26, 2018

- By Oseloka Obaze, MD & CEO

- 0 Comment

Good evening, Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen:

I know that seated amongst you are Lords & Dames – temporal and divine – great men and women of “caliber and timber,” to borrow the phrase of Chief K.O. Mbadiwe of Nigeria’s First Republic; to whom the protocol of individual introductions should have preceded my remarks this evening.

I crave your indulgence, however, to skip that otherwise warranted protocol in the interest of time.

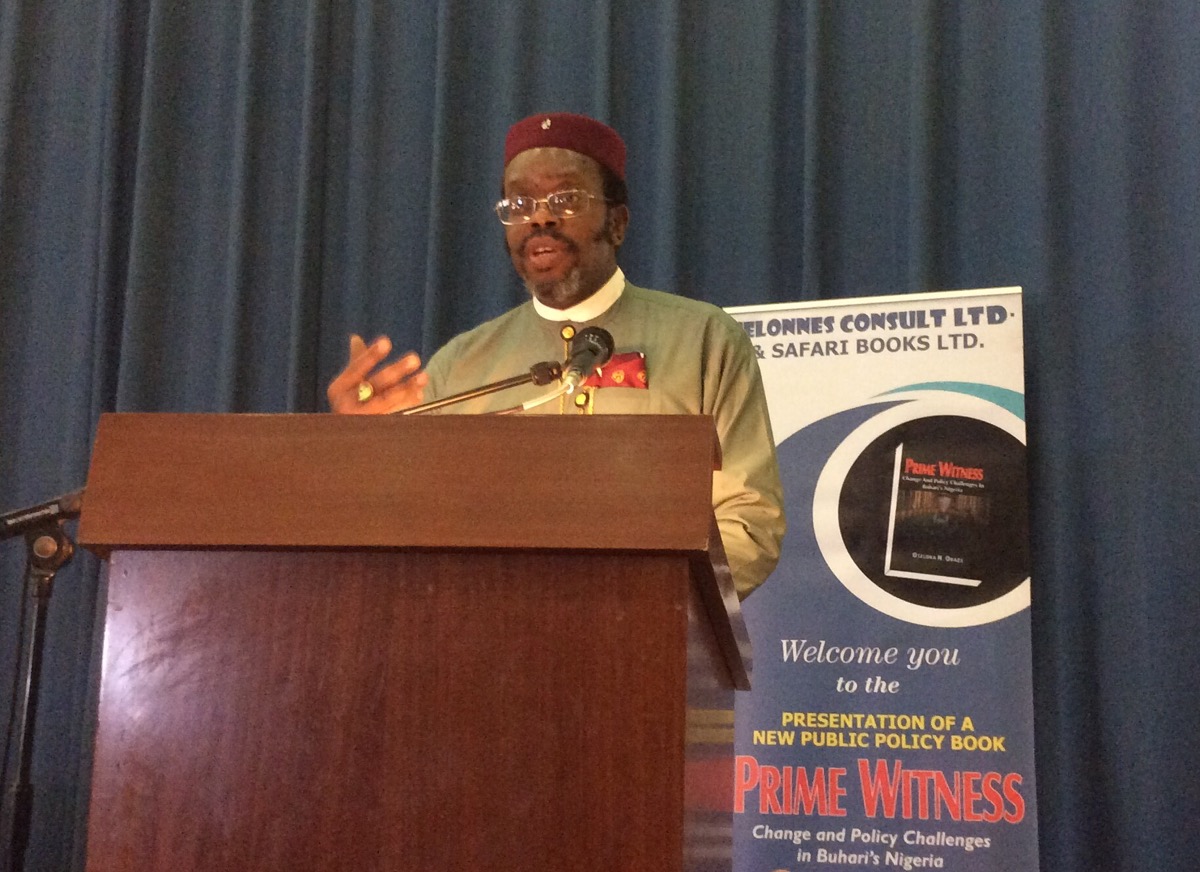

I have been given the honor and privilege as well as responsibility of reviewing Mr. Oseloka Obaze’s new book: Prime Witness: Change and Policy Challenges in Buhari’s Nigeria (2017); and I am delighted to do so.

In order to accomplish that task, I have divided my presentation into SEVEN parts: (1) A synopsis of the author’s professional career; (2) My first encounter with his intellectual output – his collection of poems; (3) My second encounter with his intellectual output – Prime Witness; (4) Summary of the guts of his book; (5) My views on his motivation(s) for writing the book; (6) My Deductions and Insights; and (7) My Exhortations.

Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen, please do not panic at what might seem a rather long list of segments to my talk today; I promise you, I do not intend to subject you (or myself), to a longwinded exegesis. I promise to avoid becoming pedantic; and to be analytical without becoming unduly esoteric.

Mr. Oseloka Obaze: A Synopsis of the Author’s Professional Career:

Top International Diplomat – at the UN – for over twenty years.

Author (Poet Extraordinaire, Scholar & Raconteur) – Four works to date and counting: (1) Co-Author of a work on the Legacy of Joseph Garba (2012); (2) Regarscent Past: A Collection of Poems (2015); (3) Here to Serve (2016); and now, (4) Prime Witness: Change & Policy Challenges in Buhari’s Nigeria (2017).

Politician (or better still, aspirant Statesman or Statesman-in-Waiting) – Former Secretary to Anambra State Government & Former Anambra State Contestant for State Governor.

Scholar, Businessman and Gentleman Extraordinaire.

Given his educational background and professional career, Oseloka Obaze appears tailor-made for two hugely consequential roles: Public Service and Public Scholarship.

The Book

My First Encounter with his Intellectual Output – His Collection of Poems:

Two years ago, I was approached by Mr. Obaze’s publisher in the U.S. to review his collection of poems, which was to be launched in the U.S. several months later. Initially, I refused to review the work, because I have never been enthusiastic about reviewing poetry books. History and social science books, novels and plays, yes, but poetry books? Not my cup of tea. That, I felt, is strictly for stargazers and gypsies!

Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy reading a good poem whenever I come across one; and I have tried my hand at composing a number of poems myself, some of which are included in my various works—novels and scholarly books. But to review an entire collection of poetic musings by someone I had never read any of his works? That was beyond the pale for me!

Mr. Obaze’s publisher in the U.S. who I happened to know, prevailed upon me, and with great reluctance I agreed to review the work and was sent a copy of Oseloka’s book of poems.

Much to my great surprise, when I started reading the collection, I was slowly but surely drawn into the spell of Mr. Obaze’s exquisite vignettes. Each new poem I read in the volume became a great pleasure and joy. I began looking forward to coming home from work and settling down, after dinner, to reading Oseloka’s collection of poems. That was how I got to the point of writing the following as part of my review of his collection of poems (quote):

“. . . Poem after poem, the quality of expression, thematic clarity, parsimony and elocution, remained solid. The dreaded verses had turned into exquisite ones. Obaze’s poetic snapshots of the past, present and future; of nostalgic pain and promise, of ancestral and national nativity and global commons, of politics and pathos, and of disappointments and hopeful ebullience; covers a wide-ranging and beguiling canvas.”

After reading and relishing Mr. Obaze’s beautiful collection of poems, I kept wondering to myself: is this a “one-time-wonder,” a “flash in the pan,” or does this gifted writer have the intellectual and creative wherewithal to deliver more goods—especially over weightier subject matter than poetry?

Prior to my reviewing Oseloka’s collection of poems, I had not read anything else by him; and, after all, at the time, he had only one other authorial feather to his cap: his co-authorship of Joseph Garba’s legacy. Here to Serve was yet to be published in 2016; but here we are today launching his fourth work: Prime Witness, published in 2017.

It was, however, because of the sweet after-taste Oseloka’s collection of poems left on my tongue, that when he asked me to review this fourth intellectual output of his, I eagerly agreed to do so; especially given that it is right up my alley: a social science work on policymaking and governance!

My Second Encounter with Oseloka’s Intellectual Output – Prime Witness:

Although I will do my best to provide a trenchant review of Oseloka Obaze’s book today, do not expect me to dissect Mr. Obaze’s book in its entirety, so you can pretend to your friends and colleagues that you have read the book! Oh no! You will have no such luck today.

I will only give you an appetizer, enough to whet your appetite for the main course – which is reading his book yourself; for as the saying goes: ‘the taste of the pudding is in the eating.’

To that extent, Ladies and Gentlemen, be sure to leave this August event with your own autographed copy of Mr. Oseloka’s book; and if at all possible, buy extra copies for family members and friends.

Read the book – from cover to cover – so you can earn not only “bragging rights,” but a solid pulpit or rostrum upon which to authoritatively learn from, discuss and critique the book yourself!

Towards the tail end of my review of Oseloka Obaze’s collection of poems, I made a statement that appears to have proven prophetic. I stated that: “. . . I have one final thought before I stay my garrulous pen. I feel disappointed even deprived that this scintillating poet did not try his hand at the novel, for as I read through his beautifully crafted poems, I could not help feeling that Oseloka Obaze might be one of the few able to [bridge] the false divide between and betwixt poetry and prose.”

Little did I realize at the time that I was making a prophetic statement; and here we are today, celebrating the “birth” of Oseloka’s “forth intellectual child;” for all literary and scholarly writers are expectant mothers!

Summary of the Guts of His Book

The purpose of every intellectual or scholarly expose—oral or written—is threefold:

To publicize the knowledge and information crystalized in the expose;

To stimulate debate and discussions over the data, perspectives, deductions and/or insights, articulated in the expose; And

To have the expose serve as a credible basis for policy formulation or implementation by a government, agency, organization or authoritative individual.

Apart from the section of Oseloka Obaze’s book, Prime Witness, that contained its: dedication, reflection, philosophy, Foreword, Acknowledgment and Introduction; the book is divided into SIX parts: A through F.

Part A, sub-titled: Governance and Politics, is made up of chapters 1 to 15;

Part B, sub-titled: Foreign Policy is made up of chapters 16 to 18;

Part C, sub-titled: Security Challenges is made up of chapters 19 to 21;

Part D, sub-titled: Constitutional Questions is made up of chapters 22 to 25;

Part E, sub-titled: Economic and Fiscal Policies is made up of chapters 26 to 35; and finally,

Part F, sub-titled: Change Mantra in Retrospect is made up of chapters 36 to 38.

These chapters constituted of a total of 299 text pages, 42 pages of Appendices and a 14-page Index.

Prime Witness is a dense work that requires very close and concentrated reading in order for the reader to grasp and maintain the trend lines of the author’s thoughts.

The analysis of policy pronouncements, projections and efforts at implementation; tends to meander from criticism to sympathetic hearing, to a wait-and-see attitude; with the consequence that, every now and again, the author’s perspective on the various policy issues, gets lost in the shuffle or becomes so muted that the reader is unsure of the author’s definitive stance.

Prime Witness is not a book for the “average Nigerian.” It is too intellectually taxing for that segment of the Nigerian population. Even for Nigerians who are university students and public policy buffs and/or aficionados, plowing through Prime Witness will be an intellectual challenge, as well it should. Its subject matters are serious, complex and demanding of intellectual acuity. It will be most useful primarily, if not exclusively, to intellectuals, scholars and those in policymaking circles; which, in all probability, might have been its author’s intention, anyway.

The Motivation behind the Book

What was Oseloka Obaze’s motivation for writing his book: Prime Witness?

Was it purely scholarly interest in deconstructing the policymaking and implementation apparatus as well as modus operandi of the current government of Nigeria?

Was it to introduce himself to the Nigerian public, in order to showcase his administrative acumen and/or policymaking skills; as a way of positioning himself for future appointments and/or elective positions in the country? After all, it is no secret that he served in the Anambra State Government and once ran for Governor of Anambra State!

Was it a disinterested academic search for policy solutions to Nigeria’s problems of governance that are, no doubt, crying out for creative solutions and willed action?

Having judiciously read Oseloka’s Prime Witness, I, feel confident in asserting that it was all of the above. And why not? The Igbo have a saying that: ‘Ife madu lulu ogoya aburo usa.’ ‘Something someone deserves or has earned is not greed or vaulting ambition.’

Having worked and thrived in the world’s largest bureaucracy—the United Nations—for over two decades; having been trained in some of the best institutions in the world, on the delicate art and craft of policymaking and implementation, negotiation, peaceful conflict resolution processes and techniques; having had to come up with feasible policy options for problems on-the-ground in conflict-ridden environments; and having had to make such policy options conceptually intelligible and persuasive—both to his superiors and subordinates; Mr. Obaze, a bona fide Nigerian patriot, may well have felt that he had little or no choice but to put his experience and expertise to use in the discourse that is his most recent book: Prime Witness.

It remains unclear to me, however, whether a forensic analysis of policy formulation, choices and the political dynamics of their successful or unsuccessful implementation, no matter how copiously undertaken, is enough to nail down the essential concern Nigerians have about “who” Muhammadu Buhari really is? What his core values, motivations, predilections, worldview, apprehension of the modern world and Africa’s/Nigeria’s place in it, sense of religious freedom, modern feminism, etc. are?

Though President of Nigeria — for the second time — Buhari remains mysterious, if not, in fact, enigmatic to most Nigerians. In fact, Obaze noted in the Introduction to his book, Prime Witness, that:

Although Buhari, served as a military head of state thirty years earlier, and had been in the democratic political fray for over sixteen years, Nigerians knew him perfunctorily, and not necessarily or always in a positive light. Little had been written about him. He had no published autobiography. Hence, it would take exactly four months into the Buhari Presidency, for his top aides, Maman Daura and Abaa Kyari, Buhari’s Chief of Staff to compel the publishing of an “authorized biography” of Buhari by Prof. John N Paden, not only to re-introduce Buhari to Nigerians, but indeed, to inform those who “had little sense of what happened in the intervening thirty years” whilst making an attempt at presenting “objective history” and a “cultural and political perspective of the current challenges of the Buhari Presidency.”

Prime Witness did not resolve that mystery, and it might well be that it could not have or was not intended or designed to do so. Interrogating the policies of President Buhari, although they do not necessarily emanate from only him, as a means of trying to nail down the persona and philosophical worldview of President Buhari, is a bit like analyzing the diagnosis and prognosis of a doctor, without knowing anything about the doctor’s medical training or area of specialization!

President Buhari appears to have more of abstract aspirations rather than concrete policies—such as the “fight against corruption;” and where there are actual policies, their questionable efficacy are more often than not attributed to the failures of the “past administration,” and/or the persisting problem of “corruption;” which is, of course, an exquisite tautology.

My Deductions & Insights

As I read through Oseloka’s Prime Witness, a book saturated with a laundry list of public policy options, critiques and prescriptions; one shortcoming struck me: it is too gentle on President Buhari, in terms of his longstanding administrative connection to previous Nigerian governments. It does not dwell enough on his incestuous relationship with past administrations; which, logically and factually, should call into serious question, the validity of his claims to a separate political identity as well as agenda.

–And this is despite the fact that Obaze hazards his concern over that matter in two brief excerpts:

“Overtime, every succeeding administration in Nigeria made combating corruption a policy plank linked to reform or change.” (p. xxiii)

“. . . the decision by the Abacha regime and by every succeeding Nigerian government [including the current one, I presume] not to implement the Pius Okigbo Report on the missing $12.4 billion Gulf oil windfall, was a policy decision not to tackle corruption in governance seriously and to foreclose on any possibility of using the findings of the report as precedence and an effective basis for tackling similar violations in the future . . .” (p. xxiv)

Perhaps, no other Nigerian writer I have read has captured with brute clarity, that incestuous relationship between Buhari and previous Nigerian governments, as does Chudi Offodile’s book: The Politics of Biafra and the Future of Nigeria (2016). In a chapter in the book, sub-titled: “The War Philosophy,” Offodile observed that:

All the regimes – military and civilian – from 1967 till date are linked and have a common ancestry. Both Generals Murtala Mohammed and Olusegun Obasanjo served in Gowon’s cabinet. Murtala was in charge of Communications, while Obasanjo was in charge of Works. They overthrew Gowon, accusing him of corruption and sundry crimes. I know the story about how Lt. Colonel Shehu Musa Yar’Adua and other middle level officers plotted and executed the coup and then invited the trio of Murtala, Danjuma and Obasanjo to take over. The important thing is that they all knew of the coup and if it failed, they would have been guilty of treason or minimally the offence of conspiracy. If there are doubts about who knew of the plot to overthrow General Gowon and who did not know, there is no doubt about who took over from him. They were members of his cabinet.

Offodile continued with his superb historical interrogation:

Buhari served as a governor and minister in the Murtala/Obasanjo military regime and Babangida was a member of the Supreme Military Council of the same military regime. Both Babangida and Abacha were key players in General Buhari’s government of 1984-85 that overthrew the civilian government of Shagari. They announced to the whole world that they were an offshoot of the Murtala/Obasanjo administration. Babangida was Buhari’s Chief of Army Staff, while Abacha was the General Officer Commanding the second mechanized division of the army in Ibadan. This same offshoot gave birth to Babangida’s administration, which in turn threw up the Abacha’s administration. Abdulsalami Abubakar finished Abacha’s tenure following his death on the 8th of June, 1998 and then ensured the return of their godfather, General Obasanjo as civilian President in 1999. President Obasanjo personally handpicked both Yar’Adua and Jonathan to succeed him in 2007.

In 2015, Buhari, a member of the old guard was elected President. He had announced in 2011 that he was done with running for President but those who desperately wanted Jonathan out of office knew they had only one card to play, which was to field Buhari. They lobbied and convinced him to run for President. He did and won.

Offodile then makes an audacious prediction:

At the end of his tenure [that is Buhari], Nigeria will remain the same and it will be clear that what Nigeria really needs is a new track whose efficacy and utility will guarantee development. At best, Buhari can only improve on existing infrastructure and perhaps create a few more billionaires. But the masses of the North and the rest of the country will remain vulnerable to poverty and disease. Did Abacha not improve the nation’s infrastructure? Buhari should know because he was Chair of the Petroleum Trust Fund set up by Abacha. So what happened? . . .

Offodile concluded that,

. . . The way to a better future for Nigeria is through decentralization and devolution of powers to proper federating units. Decentralization is not synonymous with regionalism or zonal governments, but clustering of states into zone provides better and more efficient centers of development . . . Buhari has made the point that he was not elected to change the constitution. In 2011, his party Congress for Progressive Change (CPC), promised to restructure the country if voted into power. He may have changed his mind because his new party, APC, did not make the same promise in 2015. The APC Manifesto, however, includes similar language.”

Finally, Offodile made the following prescient observation:

. . . Northern control of all arms and organs of government and every conceivable political appointment will not create wealth for the masses of northern Nigeria. It is a failed feudal practice and it is time to change to something more meaningful. Nigeria has to move from a consumption economy to a productive one that will generate resources required to meet the aspirations of over 170 million Nigerians – not less than one percent that benefit from appointments, budget padding and allied crimes.

In my opinion, Offodile’s historical interrogation as well as the policy analysis undertaken by Oseloka Obaze in Prime Witness (especially, in chapter 38 – Retroview); raises FOUR important questions about the policy focus and direction of the Buhari Administration:

Is “Nation-Building,” as opposed to “Nation-Management,” a policy focus, let alone a policy priority for the Buhari Administration? And as Oseloka Obaze observed along the same lines: “Unquestionably, Buhari had tried to forge change, but change without a focus on nation-building, that act of creating a sense of national community among disparate peoples could hardly translate to substantial transformation. Hence his change modalities often met with reservations if not resistance.”

[And what, one might ask, is the difference between the two: “Nation-building” and “Nation-Management?” Simply put: “Nation-Building” suggests that the guardians of the nation-state are committed to welding the various ethno-lingual groups that make up the modern nation-state called Nigeria into a single cohesive and patriotic nation by various means and methods—reformatory and/or revolutionary. “Nation-Management” on the other hand, suggests simply the management of the status quo, which takes for granted that the status quo is either immutable or not amendable to change; or that its transformation may not necessarily be desirable.]

Is the much ballyhooed “Restructuring” a central policy goal and objective of the Buhari Administration? Does the Buhari Administration see the fundamental value and cogency of “Restructuring” the Federal Republic of Nigeria?

Does the Buhari Administration consider it a policy necessity, never mind a policy priority, to replace or amend the 1999 Constitution of Nigeria, in order to bring about the structural changes that have been identified as necessary for the unity, political stability, modern growth and development of Nigeria? And Fourthly;

What relationship, if any, is there between a leader’s epistemological construct—of positivism versus fatalism or vice versa—and their conception of the possibility, urgency, never mind necessity for something called: development? For if a person has a worldview in which they believe that God has already ordained, and therefore, predetermined the trajectory of a person’s, community’s, society’s or nation’s life or existence, what is the use straining for and stressing over a positivist agenda such as the phenomena called: development?

And, I would like to add a caveat to the foregoing queries in this vein: even if we miraculously achieve an efficient, institutionalized “democracy,” it will not guarantee Nigeria’s self-sustainable industrial development.

Tanzania and Senegal are two African countries that have maintained democratic systems of government from the inception of their independence from Britain and France respectively, to this very day; yet, they are nowhere near the most industrially developed countries in Africa by any stretch of the imagination.

Let me briefly share with you my analytical skepticism over the popularly presumed causal relationship between “democracy” and “development.”

To begin with, I think it is empirically demonstrable that there is no such thing as “peace.” There is only “law and order.” But if it makes anyone feel better to call ‘law and order’ “peace,” be my guest! For me, the concept and/or condition of “Peace” is merely a philosophical euphemism and metaphor for “law and order.”

The truth of the matter is that behind every successful system of law and order, is the institutionalized threat of violence and/or the actual use of violence.

The “state,” through the instrumentality of government, is prosecutor, protector, “peacekeeper,” law enforcer, jailor, executioner, tax-collector and wager of war. Now, which one of the foregoing roles or activities of the “state” (via government) does not involve the threat of violence or its actual use?

For example, what gives the court system its legitimacy – its authority – may issue from statutes, the Constitution or both; but what gives the court system its effective power is its enforcement capability: the police force. Once the “law enforcement” capability of the court system diminishes or disappears, the court system becomes essentially a “toothless bulldog.” And that, in a nutshell, is what military regimes do to national court systems, unless the court system is coopted by such military regimes to operate for their purposes.

And even where the conceptual distinction between the mere existence of “law and order” and the integral presence of “justice” is made, one which I am apt to make and accept myself; the question still remains: how, for instance, is “justice” for the weak or the underdog in society to be enforced and/or safeguarded?

I, therefore, argue that the problem with Nigeria’s “modern development” is not essentially the absence of a properly functioning “democracy,” though that too has its place; but rather the absence of law and order. Law and order undergirded by the philosophical and moral force of genuine nationalism and patriotism.

The Chinese development model, has demonstrated beyond reasonable doubt, that law and order, guided by a rational, patriotic elite, not democracy as such, is the critical factor in the self-sustainable industrial development of a modern nation. India, the world’s largest democracy—modeled after Britain, ironically, following many years of non-democratic rule by Britain in colonial India—though developing industrially as well; is lagging behind China’s quantum industrial development; in spite of the fact that India is a democracy and China is not.

Please, distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen, I want to make clear that I am not advocating dictatorship or authoritarianism of the left or right; as a prerequisite for modern national industrial development; or suggesting that a genuinely policy-focused democratically elected government is incapable of carrying out fundamental national plans for modern industrial development.

I am merely pointing out that as a matter of empirical fact:

Not one of the great empire-states in human antiquity (Egypt, Babylonia, Persia, China, India, Carthage and Rome; as well as the great ancient empire-states of the Americas—the Aztec and Inca Empires), employed “democracy” as a system of governance for their stupendous developments;

The great modern industrial powers of the world, did not achieve their modern industrial preeminence through democratic systems of government either: Britain and France used their colonial empires in Africa, Asia and the Americas, as the building blocks of their modern industrial power; and the United States had the worst form of chattel slavery known to man of Africans for almost 300 years, that served as the bailiwick of its modern industrial development.

So, let no one fool us or we fool ourselves into this contemporary “sleep walk,” that it is, primarily, the absence of “democracy” that is the boogieman forestalling Nigeria’s modern industrial development.

Our science and technology, and hence, our industrial development as well as our military-industrial-complex; has lagged, and continues to lag, behind the Western World and Asia; because we have not gotten our national industrial development priorities and plans right in the context of the modern world; regardless of whether or not our system of government is a democratic one.

In fact, our so-called democratic system of government might actually be retarding our modern industrial development, but draining much-needed financial resources bankrolling bloated, redundant, corrupt, largely dysfunctional administrative bureaucracies and legislative bodies.

Still, to be fair, democracy or no democracy, historically, there have been other macro-politico-military and economic challenges we have had to face in the last five hundred years or so, as Africans, not just as “Nigerians;” that have also held us back.

We went from our respective corporate political freedoms and autonomies in the pre-modern and pre-colonial period; to the calamity of colonial conquest and subjugation, in the context of the unfolding drama of the modern Industrial Revolution, occurring in the Western World. It was, in fact, what made their colonial conquest and subjugation of us possible in the first place. The spear, the sword, the bow and arrow, were no match for the Gatling Machine gun and the cannon ball.

Then a brief window of opportunity opened in the form of political independence from European colonialism. Unfortunately, even as we emancipated ourselves politically from European colonialism, the modern industrial dominance of the Western World was so profound and ubiquitous, that we could not escape its techno-industrial, and hence, politico-economic clutches.

To make matters worse, not only did we have to grapple as best we could, with the neo-colonialism necessitated by the dominance of Western industrial technology; the attenuation of the colonial rule of the Western European powers, was replaced by the Cold War standoff between two superpowers: one the Western superpower of the United States, and the other, the Eastern European superpower of the USSR.

And what was it that distinguished them as “superpowers,” besides their large populations, large geopolitical landmasses, high-levels of industrialization and the possession of Nuclear Capability, with enough firepower to destroy the world several times over, and therefore, holding the rest of the world to ransom, if not hostage, to the threat of thermonuclear cataclysm.

We went from grappling with Western European colonial and neo-colonial dispensation, to grappling with the Cold War dispensation of the United States and the Soviet Union; both of which still entailed neo-colonial tentacles and depredations on our national cohesion, governance and development.

As if the foregoing pyrrhic victory of our political independence from European colonialism, complicated by Cold War geopolitics, was not bad enough, that already bad situation was compounded by our self-inflicted catastrophe of leadership by a self-serving, corrupt, inept, shortsighted and ethnically primordial national governing elite.

It is the foregoing, I argue, that remains our current national trap. A trap with two winch-wedges: one, self-inflicted—our corrupt and disorderly self-governance; and the other, the politico-economic, monetary and techno-military-industrial hegemony the Western World (and increasingly, China) possess in the current global scheme of things.

Exhortations:

One cannot, therefore, overemphasize the importance of the kind of intellectual cogitation Oseloka Obaze has provided us with in his book: Prime Witness. However, in our weary past, during the period of slavery in the Americas, there used to be a saying, that: “If you want to hide something from the black man, write it down – especially, in a book.” Why? Because the vast majority of black people enslaved in the Americas, could not read and write because they were not allowed to do so; and in the case of the European colonial system in Africa, did not have access to schools or could not afford them, even if they were institutionally available.

Unfortunately, in our contemporary world, if you wish to hide something from the black man, it is still best to write it down – especially, in a book. Why? Because although many of his kind can now read and write – are literate – most of his kind still won’t read. They may be literate but they are not literary.

Nigeria is currently supposedly 60% literate, which means that a least 40% of its population cannot read and write; and therefore, have no business with any writer’s book. Of the 60% Nigerians that are supposedly literate – who can read and write – I guesstimate that no more than 20% read for pleasure and/or for self-education and improvement. The remaining 40%, read only if and when they must: at work, school, occasional newspapers, public signs and documents such as driver’s license, utility bills, bank deposit and withdrawal slips, church prayer books and hymnals, as well as the Bible or the Koran (which, in all likelihood, is written in Arabic not in English).

Thus, it is within that 20% demographic that one can hope to garner a fraction of Nigerians likely to read a piece of scholarship like the one Mr. Obaze has presented us with today.

Sadly, it is the harsh truth that most of the leadership of Nigeria—top government policy and decision makers—are not regular, never mind avid readers of works such as the one Mr. Obaze has presented us with today. Their standard excuse: ‘We are so busy with the business of ruining (sorry I meant to say, running) the country; that we have little or no time for the luxury of reading such books—no matter how cogent its subject matter!

What excuse is, of course, hogwash! For example, the founder-President of the East African country of Tanzania, Julius Nyerere, translated two of William Shakespeare’s works: Julius Caesar and the Merchant of Venice into Kiswahili; and wrote a profoundly insightful work of political philosophy, titled: Man & Development, as the sitting president of Tanzania!

And in fairness to the Nigerian leaders of the First Republic—Nnamdi Azikiwe, Tafawa Balewa, Obafemi Awolowo, Nwafor Orizu, and several others; were great men of thought, erudition and letters: whether or not you agreed or disagreed with them. For as one of my favorite American philosophers—Henry Commager—once put it: “. . . It is not orthodoxy of thought or heterodoxy of thought that is the problem, but the absence of thought.” Those First Republic Nigerian leaders wrote copious philosophical and political books about history, society, government, development, democracy, federalism and so on and so forth. They wrote their autobiographies and provided an intellectual roadmap of how they got to where they got to.

Today, intellectually, among our public officials, there is a deafening as well as a deadening silence!

The need to write about ourselves by ourselves, to ourselves and for ourselves; continues, in my opinion, to be a great one. All too often, Westerners—Americans and Europeans—are the ones writing about and documenting the social, cultural and political history of Africans and other non-Europeans. Although Nigerians are one of the leading African nations at chronicling their own existential experiences and cogitative thoughts, our efforts are hardly enough on the global scale of things. So much more needs to be done, not only to fill the domestic need for such information; but to render redundant the Western cottage industry of writing about us, because of our irresponsible omission.

Closing Remarks:

Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen, permit me to suggest to you that in contemporary Nigeria, the biggest business is government; whereas in the industrially developed economies of the world, the biggest business is “big business.”

If, in the developed economies, the fear and concern is that ‘big business’ will overwhelm, or, at the very least, undermine the integrity of governance and the democratic system of government; in the developing economies, the exact opposite is the case: the fear and concern that “big government” will overwhelm and undermine “small” as well as “big” business.

Consequently, the challenge we face in Nigeria, among others, is not only how to make government and governance more effective, but how to make it less profitable as a business; and on the other hand, how to make business more profitable as well as more insulated from rent-seeking public servants: politicians and civil servants.

Once we find the right method and balance between the two, genuine statesmen and women will naturally gravitate towards the public service of government; whereas, creative and gifted entrepreneurs – men and women alike – will naturally gravitate towards private business.

Under normal circumstances, no one who wishes to become rich, offers themselves up to serve in public service—in government. Instead, they go into the private sector—into business.

Unfortunately, Nigeria is one of the countries in the world in which it is more profitable to go into government—the public sector—than it is to go into business—the private sector (Dangote notwithstanding); because, as I said a short while ago, government is the biggest business in Nigeria.

And if, per chance, you happen to have already made some money in business—in the private sector—you do your best to either get into government, in order to make even more money; or to “sponsor” those who are involved in government, so you can make even more money through government patronage of one kind or another.

It is that bastardization of government as business, rather than as a scared calling, a sacred duty – a public service – that is at the crux of our national dilemma!

Fluency of language, it would seem, is child to acuity of mind. How could it be otherwise? For words are ultimately, nothing more than thoughts and images conceived in the human mind, and then, given symbolic expression in the characters we use to capture them in longhand and digital print; for social communication and referential conservation.

The beauty of words, their subtlety, elegance, evocativeness, arcane nature and so on and so forth; attest to the facility of the human mind that is their birth parent. In the light of the foregoing, one must conclude that Mr. Oseloka Obaze, the fountainhead of both exquisite poetry and incisive scholarship; possesses a deeply philosophical mind; a mind that probes the innards of the meaning, purpose, motive-force, responsibility and consequential outcome of our existential journey.

It is, therefore, hardly surprising that Mr. Obaze set himself the task of interrogating the policy context, content and consequences of the Buhari Administration. In my estimation, Oseloka Obaze is a crossbreed between “policy-wonk” and “philosopher-king,” between salubrious poet and meticulous reporter; at once a romantic and a pragmatist, an idealist and a realist.

Some might argue that Oseloka Obaze wishes to eat his cake and have it at the same time. But for me, I see him as a fastidious “searcher for truth,” who would rather be a “discontented philosopher” in the noble tradition of Aristotle—because he is unable to find all the answers he seeks—than a “contended pig.”

At any rate, Ladies and Gentlemen, Modern Representative Democracy is nothing, if it is not essentially about two things: (1) Electoral manifestation of the “will of the people;” and (2) Accountability to the citizenry of the selfsame democratic state by the elected government of the day.

And it is to make manifest the “will of the people” through accountability that is ultimately Oseloka Obaze’s supreme objective for interrogating his “Prime Witness:” the current President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria and the repertoire of his public policies.

Thank you very much.

Copyright © 2018 Emeka Aniagolu.

This review is published with the expressed written permission of the of the author.

All rights reserved. The right of Emeka Aniagolu as the author of this publication has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright Laws of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. Other than brief excerpts for reviews and commentaries, no part of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Author.

- Post Categories

- Uncategorized

Oseloka Obaze, MD & CEO

Mr. Obaze is the former Secretary to the State Government of Anambra State, Nigeria from 2012 to 2015 - MD & CEO, Oseloka H. Obaze. Mr. Obaze also served as a former United Nations official, from 1991-2012, and as a former member of the Nigerian Diplomatic Service, from 1982-1991.

Welcome to Selonnes Consult / OHO and Associates

Selonnes Consult Ltd. is a Strategic Policy, Good Governance and Management Consulting Firm, founded by Mr. Oseloka H. Obaze who served as Secretary to Anambra State Government from 2012-2015; a United Nations official from 1991-2012 and a Nigerian Foreign Service Officer from 1982-1991.

Recent Posts

- Policy Brief No. 24-7| Overcoming Nigeria’s Legacy of Woes

- Policy Brief No. 24-6| Nigeria’s Not Too Big To Fail By Oseloka H. Obaze

- Policy Brief No. 24-5 | Nigeria’s Opposition Abet APC’s Grim Governance

- Policy Brief No. 24-4 |Blame Game Is Not Policy Game

- Policy Brief No. 24-3 | Implementing Oronsaye Report – No Walk in the park..

Categories

- #BuFMaNxit

- #EndSARS

- 2020 appropriations

- 2023 Appropriations

- 2023 buget estimates, 2024 budget estimate, FGN

- 2023 Liberian general elections

- 2024 Approriations

- Abia State

- Abuja

- Afghanistan

- Africa

- Africa’s largest economy

- AGF Malami

- Agonizing reprisals

- Alumni Association

- Aminu Waziri Tambuwal

- Amotekun

- Anambra

- Anambra Integrated Development Strategy

- Anambra state

- ANIDS

- Announcement

- Announcements

- Anonymous

- Apartheid

- APC

- APC, continuity in governance, budget performance

- Atiku Abubakar

- Bad Governance

- Bandits

- Beyond oil economy

- Bi-partisan caucus

- Biography

- Boko Haram

- Bola Tinubu

- Book Review

- Budget making

- Buget Padding

- Buhari

- Building Coalition

- Bukola Saraki

- Burkina Faso

- CAC

- Capacity building

- Capital Flight

- Career Counseling

- Central Bank of Nigeria

- Central Minds of Government

- Chief Security Officers

- Chieftaincy

- China

- Chinese doctors

- Chinua Achebe

- Civil Service reform

- Civil Society

- Civilian joint task force

- CKC Onitsha

- Clientel

- Climate Change

- Community policing

- Community resiliency

- Community transmission

- Conferences

- Consitutional Reform

- Constitutional Rights

- COP28

- Corona Virus Facts

- Corporate Exits,

- corporate social responsibility

- Cost of governance

- Coved 19 management

- Covid 19 Case Load

- Covid 19 vaccine policy

- Covid-19

- Cross political tier aspirations

- CSOs

- Culture

- Curriculum Vitae

- Customer Relationship

- Cutting Cost of Governance

- Cyril Ramaphosa

- Democracy

- Demolitions in Nigeria

- Development

- Disaster response

- Diseent

- Domestic terrorism

- Donald Trump

- Doublethink

- Ebola

- Economic Policy

- Economy

- ECOWAS

- Education

- Elections

- EMS

- Enabling environmrnt

- Endogenous solutions to conflict

- EndSARSnow

- Enugu state

- Environment

- Environmental degredation

- Escalatory measures

- EU

- Events

- Executive Order No. 5

- Fake news

- Fake news versus freedom of speech

- Farmers/Herdsmen conflict

- Fatalities

- Faux Policies

- FGN

- First Responders

- Fiscal Policy

- Fishermen

- Flooding

- Food security

- Forced Removals

- Foreign exchange

- Foreign Policy

- Full disclosure

- Gen Soliemani

- Gender inclusion

- Gender mainstreaming

- Gender parity

- Gender Policy

- General News

- Generator Country

- Genocide

- Girl-child

- Global best practices

- Global Compact

- Global housing crisis

- Global insecurity

- Global pandemic

- Global respone

- Good Governance

- Grazing areas

- Groupthink syndrome

- Habitat

- Hate Speech

- Herdsmen

- Hisbah security outfits

- History

- Housing Deficit

- human capital

- Human development capital

- Human rights violations

- Human Security

- IGR

- INEC

- Insecurity

- Inter-community conflicts

- International relations

- Interview

- iOCs

- Iran

- Iraq

- Joe Biden

- Joe Garba

- Judiciary

- Kamala Harris

- Kankara

- Kano

- Kaño State

- Katsina State

- Kidnapping

- King Louis IX.

- Kofi Annan

- Labour Unions

- Lady Chidi Onyemelukwe

- Lagos

- Leadership

- Leadership hubris

- Legislative oversight

- Lesotho

- Libel

- Liberia,

- Literary Event

- Lock down

- Malgovernance

- Mali

- Media

- Media accountability

- Migration

- militancy

- Military coups in Africa

- Millennium Development Goal

- Minister of Health, Dr Osagie Ehanire

- Misgovernance

- Mitigation

- MNCs

- Motivational Speeches

- Muhammadu Buhari

- NAFDAC

- NASS

- Nation building

- National interest

- National resiliency strategy

- National Security

- Nationalists,

- NATO

- Natural Disaster

- NCDC

- NDA – the Nigerian Defence Academy

- NEMA

- New York Times

- Niger

- Niger Delta

- Nigeria

- Nigeria Medical Association

- Nigerian Economy

- Nigerian elite, democracy

- nigerian military

- Nigerian Senate

- Nigerian Society of Writers

- Nigerian Supreme Court.

- Nigerian Youth

- Nigerian-German relations

- NMA

- Nobel Peace Prize

- Non-state actors

- Novel corona virus

- Obituary

- oil prices

- Oil subsidy

- Onitsha

- Op-Ed.

- Operational Activities

- Opposition Politics

- Oronseye Report

- Oseloka H. Obaze

- Pacesetter Frontier Magazine

- Palliatives

- Pandemic

- Party politics

- Party Politics In Africa

- Pastoral Conflict

- PDP

- PDP Governorship Candidate

- Peace and security

- PENCOM

- Pension contributions

- Peter Obi

- Petroluem policy

- philosophy

- Piracy

- Police Brutality

- Policy Brief

- Policy Making

- Policy transparency

- Political Economy

- Political economy.

- Political exclusion

- Political inclusion

- Politics

- Power and Energy

- Press Remarks / Press Releases

- Preventive measures

- Prime Witness book presentation

- Proactive Policing

- Promotions & Offers

- Public Notice

- Quarantine

- R & D

- Racial inequality

- Regional blocs

- Regional hegemon

- Regional security network

- Regulatory Policies

- Renewable energy

- Research and development

- Responsibility to protect

- Restructuring

- Rule of law

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Safety Net Hospital

- Saigon

- SARS

- SDG

- Seasonal Floods

- Security

- Sedition

- Selonnes Consult

- SEMA

- Senator Hope Uzodinma

- Senator Stella Oduah

- Senator Uche Ekwunife

- Separation of Powers

- Services

- Shale tecnology

- Shelter in Place

- Six geopolitical zones

- SMes UNIDO

- Social distancing

- Society for International Relations Awareness (SIRA)

- South Africa

- Southeast Nigeria

- Special Intervention Programme (SIP)

- Speeches

- State police

- State vigilantes

- Stay at home order

- Stay home orders

- Strategic planning

- Strength of Government

- Tampering with free speech

- Taxes

- Technology

- Tecnology

- The Blame Game

- The Peter Principle

- The Policy Game

- Think Tank

- Three Arms of government

- Three Tiers of Government

- Treason to the Constitution

- Tributes

- Tweets

- U.S.

- UN

- UN peacekeeping

- UN sanctions

- Uncategorized

- UNEP

- Ungoverned space

- Ungoverned space,

- United Nations

- United States

- Unity Party of Liberia

- Upcoming Events

- US strategic interest

- Value added tax

- Wale Edu

- Ways and Means

- West Africa and Sahel

- White House

- Women for Women

- Women in politics in Nigeria

- World Bank

- Xenopbobia

- Yemi Osinbajo

- Youth

- Zoning,

Archives

- June 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- July 2015

Contact Info

MD & CEO

Oseloka H. ObazeA301 Chukwuemeka Nosike Street, Suite # 7, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria

Phone: NG: 0701-237-9333Mobile: US: 908-337-2766Email: Selonnes@aol.com, Info@selonnes.com