Policy Briefs

Policy Brief 54/18: Chinese Silk Road; Debt Peonage for Nigeria?

- October 30, 2018

- By Oseloka Obaze, MD & CEO

- 0 Comment

Ken Chendo & Oseloka H. Obaze

Introduction

China is out to conquer the world, and many countries have fallen victim to its geopolitical game. Yet there is an emergent corollary; worries about rising global indebtedness to China. As a superpower, China continues to assert itself on the global stage, underpinning a campaign that commenced well over a decade, with its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) also known as the “Silk Road”. Nigeria, given its prevailing economic challenges, seems hell bent on joining the club of nations indebted to China. The emergent question is twofold: Does the Chinese Silk Road offer Nigeria a panacea? Or does it place Nigeria on the trajectory to a debt peonage?

China-Nigeria relations is paradoxical and defined by two contradicting aphorism. While its commonsensical that “You don’t look a gift horse in the mouth,” it is equally pragmatic to “Beware of strangers bearing Greek gifts.” China’s global game is best summed up by Quartz, “they offer the honey of cheap infrastructure loans, then attack with the sting of default when these poorer economies aren’t able to pay their interest down.”

Undergirding the Belt and Road Initiative, is a trillion-dollar loan subvention that seeks to connect countries across continents on a trade trajectory, with China at its core. The ambitious plan involves the building of railway and road infrastructure to connect China with Central and West Asia, the Middle East and Europe (the “Belt”) and creating a 6,000km sea-route connecting China to South East Asia, Oceania and North Africa (the “Road”). The number of countries, mostly African nations already defaulting on their Chinese loans is deeply alarming. In 2017, with more than $1 billion in debt to China, Sri Lanka handed over one of its ports to companies owned by the Chinese government. Now Djibouti, home to the U.S. military’s main base in Africa, seems set to cede control of another key port to a Beijing-linked company.

Some analysts have characterized China’s Silk Road and the BRI as “debt-trap diplomacy”. According to the Centre for Global Development (CGD), a non-profit research organization, loans from China by eight nations participating in BRI, namely, Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan, and Tajikistan, will translate to above-average debt. The China loan-to-debt pitfall is huge and sufficiently wide to gobble up unsuspecting nations. Sri Lanka is a stark example. The island nation was forced to cede a port to Chinese government-owned companies after defaulting on its loans totaling more than US $1 billion. The upshot of the deal signed between two state firms -the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) and China Merchants Port Holdings – allows the state-owned Chinese company to lease the port for 99 years.

Tajikistan faced a similar fate in 2011. According to the CGD report, China reportedly agreed to write off an unquantified debt owed by Tajikistan in exchange for some 1158sq km of a disputed territory. For its part, Tajik authorities said they only agreed to provide 5.5 per cent of the land that Beijing originally sought. Meanwhile, Kyrgyzstan’s debt from infrastructure projects devolved China is set to rise from 62% to 78% of the country’s GDP, while China’s share of this debt will jump from 37% to 71%. Indicative projections by the Wall Street Journal (WSJ), point to Cambodia and Afghanistan following the same trajectory and possibly owing more than half their external debt to China. The report notes that while in some instances, Chinese debts are forgiven, routinely China responds to such challenges on a case-by-case basis, thus creating uncertainties as to when they will and will forgive debts and under what circumstances they may opt to make territory grabs.

Understandably, and strictly in terms of global strategic geopolitics, these developments are not pleasing to the other contenting superpower, the United States, which prompted former U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson to assert that “Beijing “encourages dependency using opaque contracts, predatory loan practices, and corrupt deals that mire nations in debt and undercut their sovereignty, denying them their long-term, self-sustaining growth.” The paradox as Tillerson admits is that “Chinese investment does have the potential to address Africa’s infrastructure gap, but its approach has led to mounting debt and few, if any, jobs in most countries.”

U.S. Senate inclined to block IMF bailouts for Countries hamstrung by Chinese debt

Recently, a bipartisan group of 16 U.S. senators urged the Trump administration to block the International Monetary Fund (IMF) from bailing out the countries that have obtained loans from China under its infrastructure development plan. Their joint letter to Secretary of State Michael Pompeo and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin listed Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Djibouti among the countries that have accepted billions of dollars in loans from China, but are unable to repay. Relatedly, it’s noteworthy that Zambia which is seeking a US$1.3 billion bailout from the IMF already has over US$8 billion in Chinese loans.

Disbursed BRI loans, come from the $8 trillion Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that China has earmarked for developing infrastructure in friendly countries, with a view to linking them to lucrative and expanding global trade routes. Decision as to the beneficiaries as well as the scope of the loans, are entirely within China’s remit. But there is an obvious counterbalance. Although the IMF is an international lending institution, the United States remains its largest contributor with some $164 billion in financial commitments and a corresponding influence. It is thus understandable, for Secretary Pompeo to stress that Washington is watching developments. His exact words: “Make no mistake; we will be watching what the IMF does. There’s no rationale for IMF tax dollars – and associated with that, American dollars that are part of the IMF funding – for those to go to bail out Chinese bond holders or China itself.”

Nigeria – Chinese Relations

Nigeria-Sino political and economic relations go back to 1971, when the two countries established formal diplomatic relations and exchanged envoys. The period thereafter -1971 to 1998, which coincided with the denouement of Non-aligned movement, witnessed minimal economic activities between the two countries. Indeed there was a near absence of Chinese Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) inflow into Nigeria. Conversely, Western countries dominated Nigeria’s foreign political and economic relations and accounted for most of the FDIs into Nigeria, and nearly all foreign aids, grants and technical assistance received by Nigeria. In return, nearly 90% of Nigeria’s exports (mostly crude oil) went to the West.

The tides of events were drastically altered between 2004 and 2006, following the visit of the then-Chinese President Hu Jintao to Nigeria. Not only did President Hu Jintao address a joint session of the National Assembly, he also signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) establishing a strategic partnership with Nigeria. That MOU singularly marked the new phase of Nigeria-Sino relations that consequently led to China becoming Nigeria’s biggest economic partner.

Certain economic complementarities are directly responsible for the growing relationship between China and Nigeria. First, is that Nigeria is developmentally challenged given its infrastructure deficits. Second and complementarily, China has developed one of the world’s largest and most competitive construction industries with particular expertise in the civil works, considered critical for infrastructure development. The latter when combined with China’s ability to provide presumably soft loans made its expansive incursion into Nigeria relatively easy.

Contextually, China’s engagement with Nigerian was not altruistic. With China’s industrialization drive and massive inflow of FDI, and its attendant expansive manufacturing economy, required accessible and affordable oil and mineral input, which were readily available from Nigeria which is well endowed with these resources. Moreover, Nigeria’s rebased economy made it Africa’s largest economy. Accordingly, whilst China-Africa trade was a paltry $10 billion USD in 2000, by 2014, trade had expanded twenty times to $220 billion. With over $6 billion Chinese investment between 2012and 2017, Nigeria ranks second behind Egypt, as Africa’s largest recipient of Chinese investment. Naturally, Nigeria may well join the swelling club of Chinese debtors (Table below indicates 13 nations heavily indebted to China).

In his 2013 op-ed in the Financial Times, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, the then Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria, opined that “Africa must get real about Chinese ties,” while decrying the way that China operates across the continent. According to Sanusi, “China takes our primary goods and sells us manufactured ones. This was also the essence of colonialism. The British went to Africa and India to secure raw materials and markets. Africa is now willingly opening itself up to a new form of imperialism. The days of the Non-Aligned Movement that united us after colonialism are gone. China is no longer a fellow under-developed economy – it is the world’s second-biggest, capable of the same forms of exploitation as the West. It is a significant contributor to Africa’s deindustrialisation and underdevelopment.”

There is a surfeit of data showing the scale of China’s investments and influence in Africa. Indeed, the China Africa Research Initiative at the Johns Hopkins University estimates that, from 2000 to 2015, the Chinese government, banks and contractors extended well over $94.4 billion worth of loans to African governments and state-owned enterprises. [Source required] The quantum leap is glaring; rising from a few million dollars in 2000, to over $16 billion in 2013 alone. Whether these loans represent value for money or just inflow of money from the Chinese government to Chinese companies via Africa remains a matter of strident debate. Positive as these loans may seem, they also present a deleterious component, in that often, they abet corruption, as evidenced by the $600 million Chinese loan meant to fund the installation of CCTV cameras across the Nigerian capital, Abuja, but which has since been mired in corruption and scandal. This is hardly an isolated story.

The China-Nigeria narrative is meshed and further underpinned by conviction on both sides of accruing mutual benefits. Addressing a group of young students and aspiring diplomats from the Benson Idahosa University (BIU) at the Chinese Embassy in Abuja recently, the Ambassador of China to Nigeria, Dr. Zhou Pingjian, stated that China thinks of its relationship with Nigeria “In a very strategic way. If we want to grow with Africa, how can we not involve Nigeria? In your economic journey, you will need international partners and we can assure you that China is one of Nigeria’s most reliable partners in achieving its dreams…Trade is important, but investing in industrialisation is more important – that’s how you create jobs.”[Source required]

Estimates of how much China has invested in Nigeria, in terms of infrastructure, remains subjective, but significant enough to spark some positive ripples in Abuja. As President Muhammadu Buhari said last January: “Since independence, no country has helped our country in infrastructure development like the Chinese. In some projects, the Chinese committed to funding the projects by as much as with 85 per cent through soft loans that span 20 years. No country has done that for us.”

Nigeria- China Bilateral Trade and Agreements

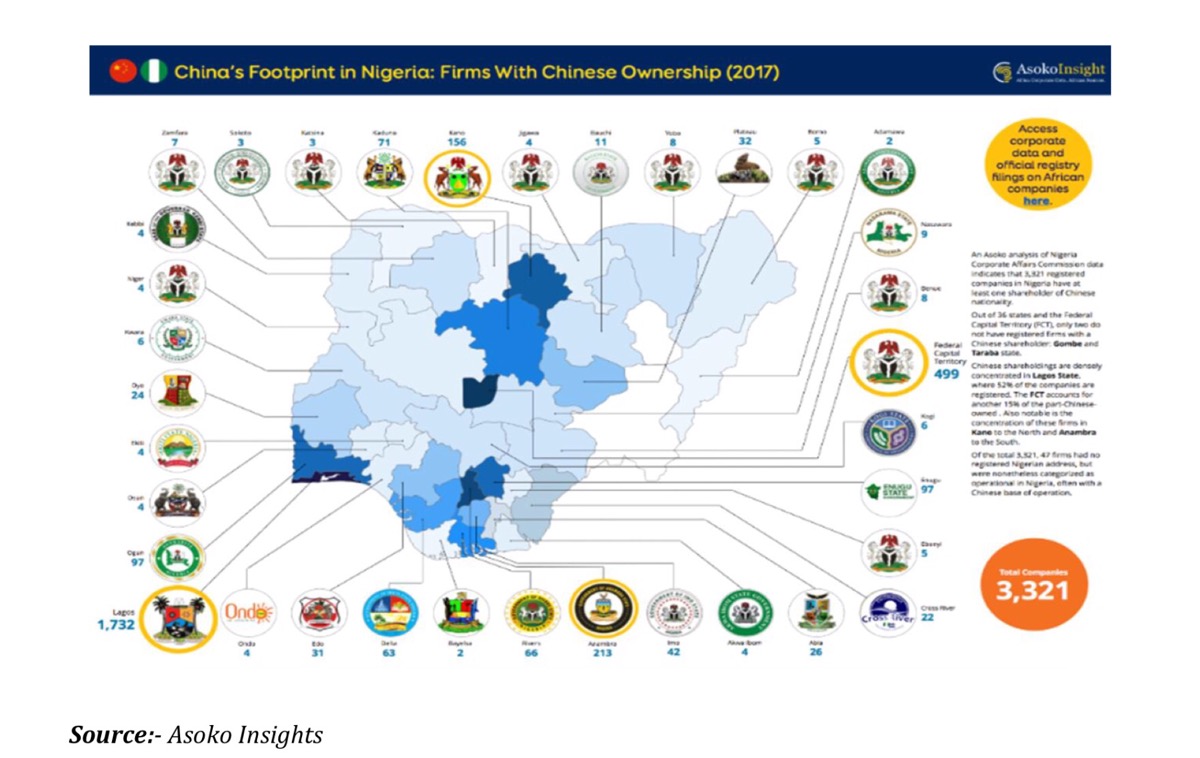

Bilateral trade between Nigeria and China has been incremental, rising every year without fail. China has a huge footprint in Nigeria. (See table below) Consequently, China remains Nigeria’s biggest trade partner, with available figures from end of 2016, indicating that the volume of bilateral trade between both countries stood approximately at US$14.7 billion. Imports from China accounted for 35% of Nigeria’s total import. Unsurprisingly, there is a trade imbalance since between 2013 and 2015; Nigeria imported 780% more from China than its exports to the Asian nation. The lopsided situation merited being accorded priority in President Muhammadu Buhari’s address at the opening of a Nigeria-China Business/Investment Forum in Beijing in 2016.

Presently, the most discernible aspects of Nigeria-China cooperation relates to construction of roads, airports and the railways — all financed through what is portrayed as sufficiently liberal loan schemes geared at addressing Nigeria’s immense infrastructural challenges. Contextually, China is spearheading efforts to modernise Nigeria’s railway through a funding arrangement that eases the pressure on the country’s financial stress in a post-recession environment. This approach which has greatly strengthened the Beijing-Abuja political alliance has presumably built trust between the two countries. The strength and value of this evolving political bond has manifested is different ways; recently been revealed at the United Nations China endorsed Nigeria’s bid to become a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council, citing Nigeria’s status as a “leading developing country.”

The Currency Swap

Similarly, Nigeria and China concluded a currency swap agreement recently, in which 16bn Renminbi (RMB) is to provide adequate local currency liquidity to Nigerian and Chinese businessmen. It’s noteworthy that since 2014, Chinese currency, the Yuan, has assumed greater prominence in world trade with some countries considering it a global reserves currency. The idea to diversify Nigeria’s foreign reserves was first mooted in 2004 by the CBN to increase the percentage of Yuan in Nigeria’s foreign reserves from 2% to about 7%. The initiative stalled until about 2016 when the Governors of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), and the Peoples Bank of China revived the initiative, with a view to assist local businesses by reducing the difficulties usually encountered in search of third currencies.

With the deal, Nigeria became the fourth country in Africa (after Ghana, South Africa and Zimbabwe) to sign on to Yuan for its trading and financial market transactions. Nigeria and China signed the agreement in Beijing on Friday, April 27, 2018. Positive as it seems, some concerned Nigerians consider the currency swap unnecessary and worry majority that the country’s foreign trade deals would be skewered toward China, which in turn, may result in economic dependence that might conflict with Nigeria’s sovereignty. Such concerns are hardly misplaced since it could lead to the expanded dumping of Chinese goods into Nigeria, with immense negative consequences given prevailing weak regulations.

Nigeria’s economic dalliance with China has elicited concerns outside Nigeria, including warnings from the U.S. government that Nigeria and other African countries should be wary of Chinese deals. As former Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, posited, “China encouraged dependency, utilised corrupt deals and endangered Africa’s natural resources… We are not in any way attempting to keep Chinese ‘dollars’ from Africa, (but) it is important that African countries carefully consider the terms of those agreements and not forfeit their sovereignty.”

Chinese Firms Dominate Africa

Grasping China’s impact in Nigeria requires how Chinese firms have been insinuated into and indeed dominates Africa’s economy. China’s huge incursion into Africa has paradoxically been referred to as “China Safari” and “China Bazaar”; terms that connote varying degrees benefits laced with sufficient doubt and disenchantment. To some dealing with China is a gamble, but one which some African states see as a necessary evil, if they must develop their infrastructure. Behind the extensive macro numbers are thousands of uncounted Chinese firms bestriding and operating across Africa. In just eight African countries, the numbers of identifiable Chinese-owned firms range between two to nine times the numbers of firms actually registered by China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), which maintains the largest database of Chinese firms in Africa. Extrapolated across the continent, the findings suggest there are more than 10,000 Chinese-owned firms operating in Africa presently. No one can say for sure—not even the Chinese government knows how many Chinese businesses are in Africa, never mind what they are doing there.

Conclusion

Prevailing concerns that China’s incursion into Nigeria might have negative consequences in the long-term cannot be over exaggerated. China-Nigeria investment relations just like any bilateral relationship, has some advantages and disadvantages. Thus, whether the Chinese Silk Road represent Eureka or a; debt peonage for Nigeria can only be determined in the near future. The pointer, for now is on the balance and the pendulum could swing either way.

Meanwhile, Chinese economic interests in Nigeria can be broadly classified into two parts: private and public. As information from the Nigerian Investment Promotion Commission (NIPC) reveals, Chinese private FDI are mostly in agro-allied industry, manufacturing and communications sectors. Correspondence is observed between countries with large Chinese natural resource investments and those with large Chinese infrastructure financing for power and transport. This nexus is explained by the compelling need to link mining deposits with power required for processing and rail and port infrastructure required for export. Nigeria, though a major recipient of Chinese infrastructure finance, received relatively small volumes of Chinese infrastructure finance during 2002 and 2005. However, in 2006 there was a major surge when China made almost US$5 billion of infrastructure finance commitments to Nigeria, an amount that accounted for some 70% of China’s total commitments to Sub-Saharan Africa for that year.

Comparatively, sectoral spread of Chinese infrastructure finance in Nigeria varies little from those on the entire Africa, with transport infrastructure projects amounting to 65.0% of all commitments followed by power with 24.0%. Chinese investment is concentrated in a few sectors that are of strategic interest to China, especially in the extractive industries. They are carried out largely by state-owned enterprises or joint ventures.

An optimal outcome from Nigeria-China relationship will depend on the policies and institutions that are put in place particularly by Nigeria to maximize the complementary effects and to minimize the competing and deleterious effects. China is virtually everywhere in Nigeria, but information about its engagement and activities remain opaque and fragmented. There is therefore, need to establish a coordinating body on China. This body, preferably a technical arm of an existing body, should be empowered to scrutinize and evaluate agreements, memoranda and any other articles of association between Nigeria and China. The ultimate objective of the proposed body is to spell out the cost as well as the benefits of Chinese-proposed projects and/or programmes. This is similar to what a legal department would do to an agreement before initialising/signing. The proposed technical committee in its assignment must have taken into consideration domestically available resources including skills and ensure that as much as possible, the local content of the agreement is high enough not only for the purpose of generating employment for Nigerians, but also to develop their technological capability.

Nigeria-Sino economic engagement represents a Catch-22 situation. Perceived short and long-term benefits notwithstanding, Nigerian Government needs to urgently institute policies aimed at maximizing the direct and indirect benefits as well as in minimizing the possible negative impacts. A litmus test for gauging the motive of FDI is to classify investments into tri-niche strata: resource-seeking, market-seeking or efficiency-seeking. Efficiency-seeking FDI is preferred to other forms, at least from the perspective of the host country. Furthermore, there is need to ensure implementation of laws and regulations in Nigeria and to ensure compliance by the Chinese investors. Such laws include labour law, corporate social responsibility laws and local content requirement. The Nigeria Labour Congress and its counterpart in the private sector should ensure full compliance with Nigerian labour laws by Chinese-owned firms. Finally, Nigeria must continue to evaluate its cumulative indebtedness to China, and its ability to amortize such debts without defaulting and without being debt-strapped unwittingly.

————-

Chendo is a Research Associate at Selonnes Consult; Obaze is MD/CEO Selonnes Consult in Awka.

NOTES

Oseloka Obaze, MD & CEO

Mr. Obaze is the former Secretary to the State Government of Anambra State, Nigeria from 2012 to 2015 - MD & CEO, Oseloka H. Obaze. Mr. Obaze also served as a former United Nations official, from 1991-2012, and as a former member of the Nigerian Diplomatic Service, from 1982-1991.

Welcome to Selonnes Consult / OHO and Associates

Selonnes Consult Ltd. is a Strategic Policy, Good Governance and Management Consulting Firm, founded by Mr. Oseloka H. Obaze who served as Secretary to Anambra State Government from 2012-2015; a United Nations official from 1991-2012 and a Nigerian Foreign Service Officer from 1982-1991.

Recent Posts

- Policy Brief No. 24-5 | Nigeria’s Opposition Abet APC’s Grim Governance

- Policy Brief No. 24-4 |Blame Game Is Not Policy Game

- Policy Brief No. 24-3 | Implementing Oronsaye Report – No Walk in the park..

-

Policy Brief No. 24-2 | History Lesson from the “Generator Country.”

By Oseloka H. Obaze - Policy Brief No. 24-1 |Nigeria’s Malgovernance, Misgovernance and Bad Governance

Categories

- #BuFMaNxit

- #EndSARS

- 2020 appropriations

- 2023 Appropriations

- 2023 buget estimates, 2024 budget estimate, FGN

- 2023 Liberian general elections

- 2024 Approriations

- Abia State

- Abuja

- Afghanistan

- Africa

- Africa’s largest economy

- AGF Malami

- Agonizing reprisals

- Alumni Association

- Aminu Waziri Tambuwal

- Amotekun

- Anambra

- Anambra Integrated Development Strategy

- Anambra state

- ANIDS

- Announcement

- Announcements

- Anonymous

- Apartheid

- APC

- APC, continuity in governance, budget performance

- Atiku Abubakar

- Bad Governance

- Bandits

- Beyond oil economy

- Bi-partisan caucus

- Biography

- Boko Haram

- Bola Tinubu

- Book Review

- Budget making

- Buget Padding

- Buhari

- Building Coalition

- Bukola Saraki

- Burkina Faso

- CAC

- Capacity building

- Capital Flight

- Career Counseling

- Central Bank of Nigeria

- Central Minds of Government

- Chief Security Officers

- Chieftaincy

- China

- Chinese doctors

- Chinua Achebe

- Civil Service reform

- Civil Society

- Civilian joint task force

- CKC Onitsha

- Clientel

- Climate Change

- Community policing

- Community resiliency

- Community transmission

- Conferences

- Consitutional Reform

- Constitutional Rights

- COP28

- Corona Virus Facts

- Corporate Exits,

- corporate social responsibility

- Cost of governance

- Coved 19 management

- Covid 19 Case Load

- Covid 19 vaccine policy

- Covid-19

- Cross political tier aspirations

- CSOs

- Culture

- Curriculum Vitae

- Customer Relationship

- Cutting Cost of Governance

- Cyril Ramaphosa

- Democracy

- Demolitions in Nigeria

- Development

- Disaster response

- Diseent

- Domestic terrorism

- Donald Trump

- Doublethink

- Ebola

- Economic Policy

- Economy

- ECOWAS

- Education

- Elections

- EMS

- Enabling environmrnt

- Endogenous solutions to conflict

- EndSARSnow

- Enugu state

- Environment

- Environmental degredation

- Escalatory measures

- EU

- Events

- Executive Order No. 5

- Fake news

- Fake news versus freedom of speech

- Farmers/Herdsmen conflict

- Fatalities

- Faux Policies

- FGN

- First Responders

- Fiscal Policy

- Fishermen

- Flooding

- Food security

- Forced Removals

- Foreign exchange

- Foreign Policy

- Full disclosure

- Gen Soliemani

- Gender inclusion

- Gender mainstreaming

- Gender parity

- Gender Policy

- General News

- Generator Country

- Genocide

- Girl-child

- Global best practices

- Global Compact

- Global housing crisis

- Global insecurity

- Global pandemic

- Global respone

- Good Governance

- Grazing areas

- Groupthink syndrome

- Habitat

- Hate Speech

- Herdsmen

- Hisbah security outfits

- History

- Housing Deficit

- human capital

- Human development capital

- Human rights violations

- Human Security

- IGR

- INEC

- Insecurity

- Inter-community conflicts

- International relations

- Interview

- iOCs

- Iran

- Iraq

- Joe Biden

- Joe Garba

- Judiciary

- Kamala Harris

- Kankara

- Kano

- Kaño State

- Katsina State

- Kidnapping

- King Louis IX.

- Kofi Annan

- Labour Unions

- Lady Chidi Onyemelukwe

- Lagos

- Leadership

- Leadership hubris

- Legislative oversight

- Lesotho

- Libel

- Liberia,

- Literary Event

- Lock down

- Malgovernance

- Mali

- Media

- Media accountability

- Migration

- militancy

- Military coups in Africa

- Millennium Development Goal

- Minister of Health, Dr Osagie Ehanire

- Misgovernance

- Mitigation

- MNCs

- Motivational Speeches

- Muhammadu Buhari

- NAFDAC

- NASS

- Nation building

- National interest

- National resiliency strategy

- National Security

- Nationalists,

- NATO

- Natural Disaster

- NCDC

- NDA – the Nigerian Defence Academy

- NEMA

- New York Times

- Niger

- Niger Delta

- Nigeria

- Nigeria Medical Association

- Nigerian Economy

- Nigerian elite, democracy

- nigerian military

- Nigerian Senate

- Nigerian Society of Writers

- Nigerian Supreme Court.

- Nigerian Youth

- Nigerian-German relations

- NMA

- Nobel Peace Prize

- Non-state actors

- Novel corona virus

- Obituary

- oil prices

- Oil subsidy

- Onitsha

- Op-Ed.

- Operational Activities

- Opposition Politics

- Oronseye Report

- Oseloka H. Obaze

- Pacesetter Frontier Magazine

- Palliatives

- Pandemic

- Party politics

- Party Politics In Africa

- Pastoral Conflict

- PDP

- PDP Governorship Candidate

- Peace and security

- PENCOM

- Pension contributions

- Peter Obi

- Petroluem policy

- philosophy

- Piracy

- Police Brutality

- Policy Brief

- Policy Making

- Policy transparency

- Political Economy

- Political economy.

- Political exclusion

- Political inclusion

- Politics

- Power and Energy

- Press Remarks / Press Releases

- Preventive measures

- Prime Witness book presentation

- Proactive Policing

- Promotions & Offers

- Public Notice

- Quarantine

- R & D

- Regional blocs

- Regional hegemon

- Regional security network

- Regulatory Policies

- Renewable energy

- Research and development

- Responsibility to protect

- Restructuring

- Rule of law

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Safety Net Hospital

- Saigon

- SARS

- SDG

- Seasonal Floods

- Security

- Selonnes Consult

- SEMA

- Senator Hope Uzodinma

- Senator Stella Oduah

- Senator Uche Ekwunife

- Separation of Powers

- Services

- Shale tecnology

- Shelter in Place

- Six geopolitical zones

- SMes UNIDO

- Social distancing

- Society for International Relations Awareness (SIRA)

- South Africa

- Southeast Nigeria

- Special Intervention Programme (SIP)

- Speeches

- State police

- State vigilantes

- Stay at home order

- Stay home orders

- Strategic planning

- Strength of Government

- Tampering with free speech

- Taxes

- Technology

- Tecnology

- The Blame Game

- The Peter Principle

- The Policy Game

- Think Tank

- Three Arms of government

- Three Tiers of Government

- Treason to the Constitution

- Tributes

- Tweets

- U.S.

- UN

- UN peacekeeping

- UN sanctions

- Uncategorized

- UNEP

- Ungoverned space

- Ungoverned space,

- United Nations

- United States

- Unity Party of Liberia

- Upcoming Events

- US strategic interest

- Value added tax

- Wale Edu

- Ways and Means

- West Africa and Sahel

- White House

- Women for Women

- Women in politics in Nigeria

- World Bank

- Xenopbobia

- Yemi Osinbajo

- Youth

- Zoning,

Archives

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- July 2015

Contact Info

MD & CEO

Oseloka H. ObazeA301 Chukwuemeka Nosike Street, Suite # 7, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria

Phone: NG: 0701-237-9333Mobile: US: 908-337-2766Email: Selonnes@aol.com, Info@selonnes.com